When you dope you should be done with the sport, for life

Cheaters should be banned for life from athletics, and that should even include being allowed to hand out medals to kids at a track meet

Each year in Ontario at the OFSAA Track and Field Championships, the organizers invite esteemed guests to present medals to the kids who make the podium. Most of these presenters are former OFSAA champions, and it’s nice that the organization is trying to connect the past with the present at each championship. Track and field, like any other sport, needs to create and maintain traditions and a sense of history in order to continue to be relevant.

This year, OFSAA invited two dopers to present medals: Cheryl Thibedeau and Tony Sharpe. I know what you’re probably thinking: “who are these people,” or, if you are a diligent follower of track, “but they got caught for doping nearly 30 years ago!” Like thieves, once a doper, always a doper. If you cheat in track, you should own that inglorious distinction for the rest of your running life.

We ran stories on both disgraced former sprinters being asked to hand out medals. It’s not clear whether OFSAA asked Thibedeau not to show up, or if she decided on her own that it was a bad idea (she claims the latter, but only after an outcry on social media against her), and she did not end up participating. Sharpe attended and presented medals, as he’s done at the OFSAA championships in the past.

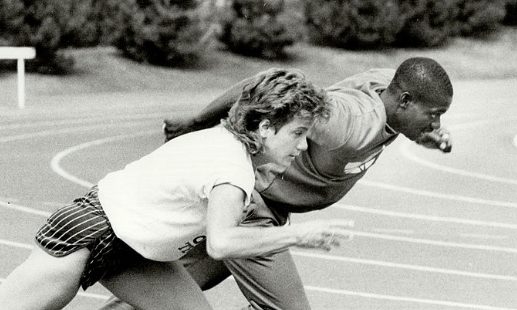

Both athletes were sprinters with Charlie Francis’ notorious training group in the 80s. Francis was Ben Johnson’s coach, and was at the centre of the rampant steroid use by his athletes during that period. If you’re old enough to remember, Johnson’s 100m win in Seoul was one of the greatest moments in Canadian sports history. His disqualification three days later is a national humiliation still felt today.

Thibedeau as a standout high school sprinter in Thunder Bay who won multiple OFSAA medals. Then she came to Toronto and joined Francis’ group. She was an alternate on the 1988 Olympic women’s relay team.

Then the Ben Johnson debacle unfolded, unravelling Canada’s Olympic identity. Francis’ group was put in the spotlight.

Thibedeau was called in testify during the Dubin inquiry, where she first admitted to doping. If you want to know more about the inquiry, take a listen to the CBC’s archived radio piece. They called the Johnson affair the “shot heard around the sports world.” Well played, CBC.

Sharpe actually won a bronze medal in the ’84 L.A. Olympic Games (on a team with Johnson; many have forgotten that Johnson was allowed to keep his ’84 medals in the 100m and 4x100m, although all anyone wonders is if he was doping at the time as well). In 1988-89, Sharpe was also found to have used steroids under Francis and was suspended. He was reinstated in 2012 after an arbitrator found that Sharpe showed “sincerity, contrition, remorse and a passion for the sport of track and field and the promotion of drug-free sport.” Basically, Sharpe said all the right things and, because he was only popped with steroids once, he was allowed to return to the sport as a coach.

Thibedeau wasn’t so remorseful, it seems. After everything she went through, she tested positive in 1992 for anabolic steroids and was banned for life from the sport.

When it comes to doping, I take a hardline stance. I am a firm believer that today the sport should have a one-strike policy: you dope and you’re done with athletics. Forever.

Athletics is in crisis. It’s hard to trust any extraordinary performance on the track or the roads. That lack of trust is ruining the experience for fans, which will significantly hurt the level of interest future athletes will have in coming to track and field over, say, soccer or basketball (remember that Andre De Grasse wanted to be a basketball player, not a runner). Instead of being excited about say, the women’s 10,000m final in Rio, where Almaz Ayana ran one of the greatest races in Olympic history, many are now cynical. That performance was incredible, leading quite a few on social media asking if it was probably just unbelievable. How do you sell a sport when it’s been poisoned by cynicism?

Thibedeau actually responded to her OFSAA situation on a Trackie.com message board, saying:

“Yes, almost half my lifetime ago, I made a very big mistake. I was given an unwarranted lifetime ban from my sport. I did not make excuses, I simply stayed away for 21 years.”

What’s interesting here is that she calls two doping bans a single “mistake.” Taking steroids when you’re an elite athlete is not a lapse in judgement. It’s not, say, locking yourself out of your apartment or sending a mean email about a person to that person. We need to stop discussing it as though it were something that everyone of us could have done in as a momentary error in judgement. It’s a willful attempt to cheat others competitively and financially at the highest level. It’s lying and cheating, plain and simple. Just ask any athlete who would have won a gold medal but were beat by a doper if their life would have been different had the doper not been in the race. Making national teams, placing and winning medals changes the lives of athletes. By doping, Thibedeau stole opportunities from other honest athletes. And she also revealed that she was willing to lie to yourself, something she seems to continue to do today.

It’s bizarre that even after Thibedeau was raked through the coals very publicly at the Dubin hearing, humiliated and banned for cheating–and then, after being given a second chance–she did it again.

Thibedeau’s response is telling and typical of a cheater. She’s not really willing to own what she did, sidestepping it by calling it a “mistake.” She also says her punishment was “unwarranted.” I imagine Thibedeau is alone in thinking that her lifetime ban after being caught for doping twice was unfair.

I’ve requested the details on Thibedeau’s 2013 reinstatement from the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport (CCES), the organization that advices Athletics Canada on doping bans. I’m curious to see if they actually ruled that her ban was “unwarranted.” I’ll update this post when I hear a response.***See update below.

According to the rules of their respective reinstatements, both Sharpe and Thibedeau are now allowed to coach. In Sharpe’s case, he said all the right things at the time, and was never busted for cheating again after all the humiliation back in 1988. Since returning to coaching in 2012, Sharpe has been credited with developing some great sprinters, including Andre De Grasse, and focusing equally on promoting academic standards with his young athletes, as evidenced by this warm and fuzzy Globe and Mail mini-doc made in the lead up to the Rio Games:

Note that the Globe editors didn’t bother mentioning that Sharpe served a doping ban, as it would have tainted this perfectly inspirational narrative.

Whether you think that’s maintaining an unfortunate connection between our country’s darkest sporting moment or a triumphant tale of why second chances are important is up to you to decide.

Sharpe’s appearance at high school track and field championships is complicated. If he were a doper in today’s athletics world, I would have no patience for him. We’ve watched track and field erode because of cheaters and it’s time to take a strong stance against them before it’s too late (and it may already be). But in fairness to both Sharpe and Thibedeau, they were caught up in a culture of cheating at a time when it seemed like everyone was doping (and as Johnson has claimed, perhaps everyone was). But it could be argued that today’s climate is no different. When looking down the line today, Canadian athletes will no doubt be facing competitors that are doping. Does that make it OK for them to cheat?

Because of Sharpe’s past, he must be careful. One misstep with an athlete and he will undo all of that rebuilding. It’s up to him to accept a honorific like handing out medals at a children’s track championship. And it’s up to OFSAA and the parents of these children to decide if this is the sort of role model they want to celebrate.

But Thibedeau’s situation is different.

In 1992, she disregarded her past experience and decided to cheat once more, taking drugs again on her own accord. And for that she has no place in our sport. Not then and not even today, on any level. Not even handing out medals to kids. In fact, especially not that.

UPDATE (June 12, 2017):

A spokesperson from the CCES looked into Thibedeau’s case and got back to me with the details, which differ from Thibedeau’s claim that they saw her punishment as an “unjust ban” and that she was “completely reinstated early 2013.”

They indicated that, yes, she had applied for reinstatement in early 2013. “Ms. Thibedeau had her period of ineligibility end, without any restrictions, on April 15, 2013,” said the spokesperson via email. “There was no conclusion by the CCES that the ban she served was in any way “unjust” nor was she reinstated.”

They clarified that her case was evaluated based on the 2009 anti-doping code, and that they decided that, at 20 years, her sanction had been satisfied. Based on the 2009 anti-doping rules, an athlete committing a second offence, as she did, “would receive a sanction of between 8 years to a lifetime ban.” The CCES decided then that her ban had come to term in 2013. So, she wasn’t “reinstated” but merely her sanction ended on April 15, 2013. They also pointed out that at no time was she banned from coaching or handing out medals at ceremonies.

––––––––––––––––––––––

Michael Doyle is the editor-in-chief of Canadian Running. Each week he blogs about what’s exciting, upsetting, enraging or engaging about what’s going on in the running world.