Feature: Gérard Côté – Canada’s greatest Boston marathoner

This year, nearly 2,000 Canadians will run the Boston Marathon. Running historian Roger Robinson throws new light on Gérard Côté, Canada’s most successful Boston marathoner.

Gentlemen! Gentlemen! One beer! One cigar! Then we can talk about the race! – Gérard Côté to journalists after his fourth Boston Marathon victory, 1948

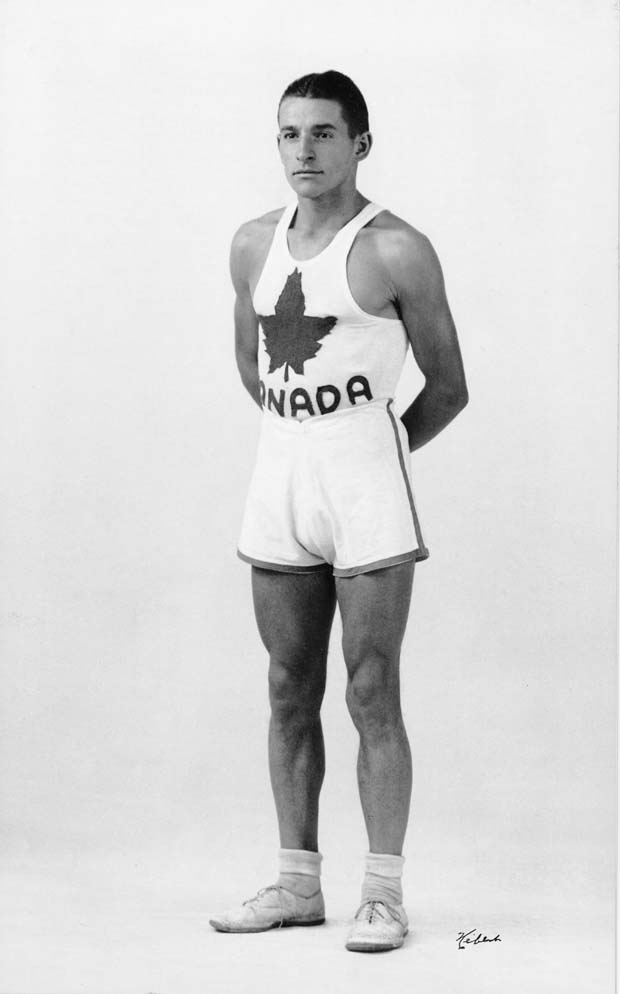

Gérard Côté of Quebec is famed in Boston lore for his post-race cigars, mischievous grin, all-night partying, spiffy dressing and his carefree Gallic sparkle. He created that image and enjoyed living up it. But it takes more than cigars and sharp suits to win the Boston Marathon four times. It takes more than beer and mischief to compete at top level in marathons for 19 years, compile a resumé of 112 victories in 256 races, and set records in two different sports.

It takes a lot more than carefree sparkle to do all that from beginnings as one of 15 children on a small, struggling farm. This was especially impressive for the undersized boy who had to leave school at 11 years old when his mother died to take on manual work to help support his family.

Over the course of his four victories, the Boston papers called the lively and diminutive French Canadian “dandy,” “nonchalant” and “debonair.” Yet in training he pushed the limits of what was then believed to be endurable. In racing, he was tactically adroit, physically resilient and good at winning. He won Boston more times in its 118 years than anyone but Clarence DeMar (seven wins), and Bill Rodgers (who also won four times) and placed in the top eight 13 times, up to age 39.

But there is more to the Gérard Côté story than laurel wreaths and big cigars.

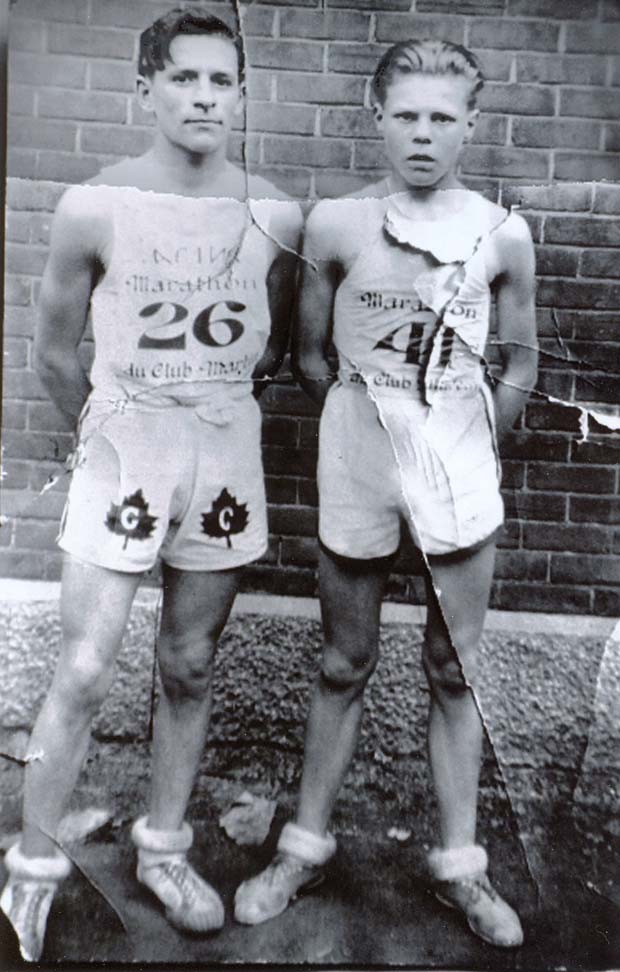

It began with a boyhood at the village of Saint-Barnabe, near Saint-Hyacinthe, in rural Quebec. The physically small Côté found something he was good at that would help the family–running long-distance errands and messages for his parents. He added upper-body strength as a teen, working construction jobs for his father and dabbled in boxing.

“I was about 85 lb. at first, no bigger than that, but I was very strong,” he recalled when interviewed at age 69 for David Blaikie’s seminal book Boston: The Canadian Story (1984).

Côté found he liked the “road work” for boxing better than the punching. He began to run well in local races, and caught the eye of an astute old professional ultrarunner, Pete Gavuzzi, who had been one of the stars of the punishing coast-to-coast Trans-American Foot Race in 1929. Gavuzzi steered him on a regimen of long runs that surpassed the training even of DeMar, the pioneer of high mileage. “You had to follow [Gavuzzi] if you wanted to learn something,” Côté told Blaikie.

“Sometimes I was running with him 35, even 40 miles [56–64k].”

In 1935 he went to New York to run the Yonkers Marathon, placing 12th in his first attempt. Côté was hooked. He ran Yonkers and Boston every year from 1936 to 1940. He improved year-by-year at Boston, from 2:54:22 in 1936 to 2:28:28 in 1940. He became absorbed into the marathon’s intense and compelling culture. In the late 1930s it was a small world of tough men from modest manual worker backgrounds, who were competitive yet tight-knit with each other, bonded by the shared sense of significance and heroism that the marathon brought into their lives.

A Côté story typifies their mutual respect. At the Yonkers Marathon in December 1940, he was on pace to break the course record. But it belonged to his marathon colleague Pat Dengis, who had recently died in a plane crash. When Dengis’s widow called out from the side of the course that he was going to beat her husband’s record, Côté checked his watch, slowed to a jog, and did just good enough to keep first place. The Yonkers record (2:34:27) stood in Dengis’s name until 1955. “It was not a big thing. I could have made about 2:30, I think,” Côté said.

Marathon fields were small – 210 at Boston in 1937 was the highest in that era, as recorded in Tom Derderian’s Boston Marathon: A History – but crowds were large and the newspaper coverage was massive. So when Côté won in 1940, he revelled in his sudden, massive fame, and always liked to celebrate with those that raised his status from lowly manual worker to sports celebrity. “He ordered scotch and port wine from room service for himself and the reporters,” writes Derderian.

He had earned it. On top of Gavuzzi’s long runs, he added snowshoe racing in winter, and went to Boston in 1940 as world snowshoe record holder for 10 miles.

Elite athletes today get different treatment on race day. Runners in 1940 were told to catch the 7:55 a.m. train from Boston to Hopkinton. They assembled in the overcrowded Lucky Rock Manor Inn. They were summoned one-by-one for a compulsory medical check. They had to provide their own pins for bib numbers. There were no split times on the course, except at irregularly located checkpoints.

In the 1940 race, no one seemed to want to lead, Côté said, so he took it until the defending champion Ellison “Tarzan” Brown went ahead at halfway, followed by 1935 winner Johnny Kelley. By the Newton Hills, Côté was assessing his chances.

“I noticed Tarzan from behind and he was not running well. His legs seemed to be tying up… Along came Scotty Rankine, full of running. Then I began to perk up,” he told the Boston Post, cited by Michael Ward in Ellison “Tarzan” Brown.

As Brown faltered, Rankine charged up Heartbreak Hill (which was just acquiring that name) to do battle with Kelley. From Côté’s perspective 180 m back, they were wearing each other out. With a precision strike at seven kilometres to go, the Canadian surged past them into the lead.

“My legs were working like pistons. I felt like waving to all the crowd… I just ran, with no thought for the record, but only to win,” Côté told the media. His only problem now was the clogged traffic on the course. “There were more official cars than there were runners and when Côté started to pour it on in his final burst, the race began to look like the Indianapolis speedway,” wrote the Boston Globe.

Côté was unperturbed. His rivals were broken, more than three minutes behind. He could slow to a jog and relish the moment. “He could salute the jammed ranks of spectators… He crossed the line with the broadest of grins,” wrote the Boston Herald.

Despite those celebratory final 200 metres, his 2:28:28 was a course record.

Côté had won Boston and Yonkers, North America’s top two marathons. He won Boston again in 1943, 1944 and 1948. His Boston wins gave him the world’s second fastest time in 1940, and the world’s fastest in 1944. Those dates are significant.

“Many feel that, had the [Olympic] Games been held in 1940 and 1944, he would have been a prime contender,” is the summary by David Martin and Roger Gynn in The Olympic Marathon.

The Second World War denied him the opportunity.

Côté married in 1941, and enjoyed a few months of celebrity in Saint-Hyacinthe, where a grill was named for him, and he was

able to give up his newspaper distribution business. “He was hired to mingle with customers,” writes Blaikie. “He would light his pipe or puff a cigar or quaff a beer with them.”

In Europe, Canada was key to the Allies’ survival. Côté was called up in 1942 and served as a physical education instructor, and then at a munitions plant. He often ran the 40 kilometres between the plant and his home in Montreal. Those were distracting years, but after placing fourth and sixth at Boston in 1941 and 1942, he was ready again.

In Europe, Canada was key to the Allies’ survival. Côté was called up in 1942 and served as a physical education instructor, and then at a munitions plant. He often ran the 40 kilometres between the plant and his home in Montreal. Those were distracting years, but after placing fourth and sixth at Boston in 1941 and 1942, he was ready again.

His 1943 victory was achieved despite excruciating pain from an Achilles tendon injured five days before the race. He gutted it out, against Kelley and a strong American field, and won, three seconds faster than in 1940.

The delighted Canadian Army used Sgt. Côté’s pictures for publicity, but quickly retracted when the public protested about pre-ferential treatment. In 1944, Côté took leave and ran privately, sponsored by a Montreal restaurateur. Back in Boston, determined to win once again, Côté found Kelley determined to break out of his perpetual runner-up role, attacking savagely with 3K to go. Côté pulled back the gap. “They raced through Kenmore Square shoulder to shoulder as packed thousands cheered. Somebody had to break,” reported the Boston Record. Côté’s perky personality concealed a steely will. It was Kelley who broke, and Côté collected his third win.

The Army was not pleased, and shipped him to England. He was there for the duration, winning three English marathons before his discharge in 1946. It’s a little cruel to say so, but Kelley’s now-legendary victory in 1945 owes at least something to the sensitivities of the Canadian Army.

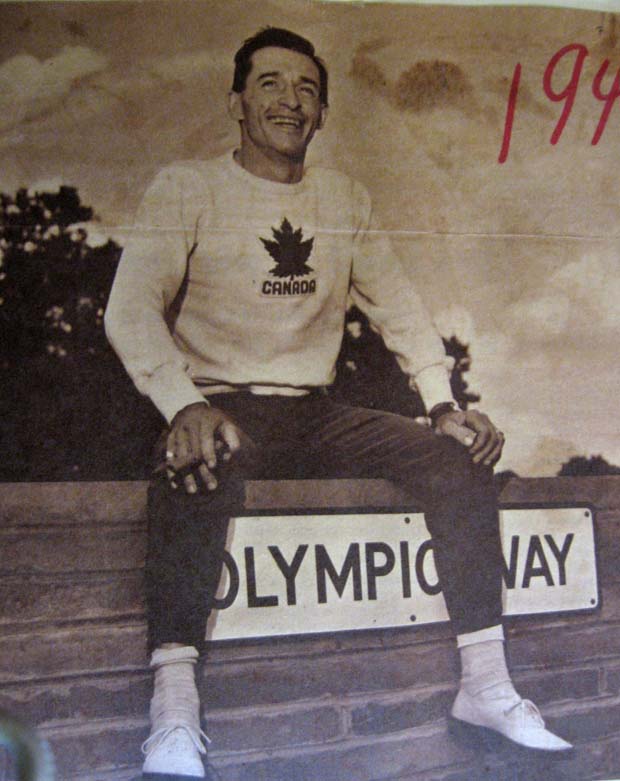

Côté was not done. He placed third and fourth in 1946 and 1947, then in 1948 sealed his place in Boston history with his fourth win.

He didn’t really want to win, he said afterwards, disarmingly, as his focus was the upcoming Olympic Games, and he wanted only a good training run. But it turned into a contest against Ted Vogel that Boston historians love to describe in lurid terms as a near punch-up. Vogel, after wartime navy service, was a university student, so there may have been some class tension behind the heel-clipping and elbow-nudging that Vogel claimed. Or perhaps it was only the common problem of a tall long-striding runner duelling with a shorter one. “We bumped a little bit twice but it was an accident,” said Côté innocently. “If you try any more of that stuff I’ll slug you,” Vogel reportedly growled, though Côté denied it. “I do not believe he said that. What would we do? Stop in the middle of the street and fight?” he said. Even Boston’s own official history, in the race’s annual media guide, claims “the duel on occasion bordered on the unsportsmanlike,” a charge for which there is no substantive evidence.

Côté ran one marathon too many before the London Olympics, suffered from the warm conditions and hilly course, and managed only 17th, in 2:48:31, three places behind Vogel and one place behind fellow-Canadian Lloyd Evans. He was even more disappointing in the British Empire Games in Auckland in 1950. In heavy rain he finished in 11th in 2:51:58. One place behind him was New Zealand’s Arthur Lydiard, on his way to immortality as a coach.

Côté still loved Boston. At the tail end of his career, he was still running in the 2:40s. His last was 1955 when he was 41. Boston had become a fully international race. Since Côté, only two Canadians have won Boston: Jerome Drayton in 1977 and Jacqueline Gareau in 1980. He was there to see Gareau win, as the guest of honour on the 40th anniversary of his first victory.

In his later years, Côté often attended races. And he kept running. “He still runs hard… A slower gait would do for health, but that’s not in his nature,” reported Blaikie in 1982. His death at age 79 in 1993 attracted little attention. How different that might have been if his four wins were valued in Canada as highly as Bill Rodgers’ are in America. Or, given his world rankings and competitive flair, if the Olympic Games had been held as scheduled in 1940 and 1944. Canada might have been mourning Gérard Côté as a double gold medallist as well as four-time Boston champion.