Feature – Fade From the Front: the Rob Watson story

Rob Watson is going for broke in his pursuit of the Canadian marathon record.

Rob Watson sits in the lobby of the Fairmont Copley Plaza, one of Boston’s ritziest hotels, in warm-up clothes and flip-flops. If it was any other weekend, the lanky, boyish looking 29-year old would be out of place. But as he sits there, nursing a bottle of sports drink and gazing up innocently at the gilded ceilings, the lobby is abuzz with lean figures in track suits. It’s Patriots’Day weekend in Boston, where for a few days distance runners are treated like kings.

“I have $45 in my bank account right now,” Watson says. He won’t talk about the exact amount of his appearance fee, but it’s clear that he’s not accustomed to the treatment he’s received from the Boston Athletic Association. “Most races will f ly you out, and they’ll put you up in a hotel of some kind,” he says. “When I checked in and went up to my room I was confused, because there was only one bed. Usually, we get put in a room with another runner. This will be the first time I might get a good night’s sleep before a marathon.”

The primary sponsor, the insurance company John Hancock, was instrumental in getting Watson to Boston. Hancock is owned by Manulife Financial, a Canadian company, and they wanted a domestic elite at their marquee sporting event. “Usually, the organizers will bring you in on the Friday or the Saturday, there will be a media conference, and then you race the next day,” Watson says. “They brought me in on Wednesday, and they even flew in my brother Pete and his wife.” Pete Watson, a former elite runner himself, has been coaching Rob since early 2012. They are encouraged to attend the various marathon week activities. Rob meets some of his heroes, who are remarkably approachable. Grinning, he poses for a picture with Rob de Castella. He discusses running the Newton hills with Bill Rodgers, and his race strategy of fading from the front with Steve Jones. Watson has become a student of the sport, and models himself after these golden age marathoners.

Related Articles

Read Watson’s blog for Canadian Running from the IAAF world championships in Moscow

When asked about his goal for the race, Watson smiles, then hesitates. An entourage of Kenyans stroll by in the lobby. A man with a video camera backtracks, filming the figure at the centre of the entourage. The slight and disarming individual in the teal warm-up suit is reigning Boston champ Wesley Korir. Watson refocuses. “I want to finish in the top 10,” he says, as if he’s admitting a long hidden secret. “Boston isn’t so much about time, so I’m not going to worry about that. I’m not running for time on Monday, I’m racing for place,” he says, that grin shining through once again. No Canadian has placed in the top 10 at the Boston Marathon in 27 years.

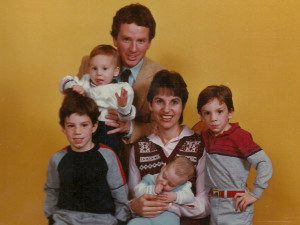

Robin Watson was the fourth of five boys to grow up in the idyllic Old South neighbourhood of London, Ont. Rob’s parents were role models for the boys growing up. “My folks have always been recreational runners,” Watson says. “My mom was good on the track. My dad ran nine marathons.” But the most significant inf luence on Watson’s running career has been his big brother, Pete. “He was always the best runner in school,” Watson says. “When I was six years old, the family went to the Forest City road races in London to watch Pete race. When we got there I didn’t want to just sit and watch him run. I wanted to run with him. That was my first race, a 10k. I ran something like 57 minutes.” Until Rob was a teenager, the Watson family were always travelling around southern Ontario to road races.

By age 13, Watson had become preoccupied with socializing and soccer. “I didn’t do track until the 11th grade. I did run cross-country, but I was terrible at it,” Watson admits. “In the ninth grade I was near last place at the city championship race. I was just doing it to get out of school and to be with my friends I was lazy.” But when his brother Pete, who was wrapping up his last semester in the ncaa for West Virginia University, started feeding him workouts, Rob started to show his potential.

Combined with a big endurance engine and an uncanny ability to suffer for long stretches, Watson became a top steeplechaser in his oac year (Grade 13). He was approached by some of the best Canadian varsity programs, including coach Dave Scott-Thomas at the University of Guelph, but Watson opted to follow in his brother Pete’s footsteps, accepting a scholarship at West Virginia.

After a rocky year, where Watson saw the wvu track program get cut, he once again found himself under Pete’s mentorship. Rob joined Pete in Colorado, where he was living at the time, and Pete became his informal coach for the summer. Pete introduced him to former ncaa champion Bryan Berryhill, who was coaching the track and cross-country teams at Colorado State. That fall, Watson headed an hour north of Boulder to Fort Collins to run for CSU.

By his senior year, Watson was struggling to balance school and partying. “I thought I was working hard because I was running 100k a week and going to the weight room here and there,” Watson says. “But I was still out drinking two nights a week and constantly eating junk food.”

In 2007, Watson made the final in the steeplechase at the ncaa championships. He was graduating with a degree in history and he is candid about his time in university. “I never really liked school,” he says. “I was there to socialize and be on the track team.” Then Watson got a phone call from Dave Scott-Thomas, who had been tracking his progress since high school. “He asked me if I wanted to keep running,” Watson says. “I wasn’t ready to join the real world, so I said yes. My only other option was to move to Korea to teach English for a while. I wanted to keep having fun.”

Guelph seemed like the perfect fit. Still living in the house that he grew up in, Watson’s parents were now just one hour away down Highway 401. He moved into an apartment with a group of young runners, including Beijing Olympian Taylor Milne, and began to train for the 2009 iaaf world championships in Berlin.

Looking down the line on the track in Berlin, Watson realized that he was in over his head. “At Worlds, Robbie got a reality check,” Pete says. “Most of the guys in his heat could run the steeple faster than he could run a straight-up 3,000m.” After a year of obsessing over standards, followed by a disappointing exit in the preliminary round of the world championships, Watson was fatigued. He was done with the track. He started to think about the road.

In the fall of 2009, Scott-Thomas and Watson sat down and discussed the marathon. “We had Reid Coolsaet and Eric Gillis migrating that way, so we had some other guys in Rob’s wheelhouse,” Scott-Thomas says. Watson was enthusiastic about the move up to the event. “I love the recreational and community side of road racing,” he says. “I’d always been a big mileage guy, so jumping up to the marathon was an easy choice.”

But his place in the group and the style of training that Scott- Thomas had them doing weren’t conducive to where Watson was in his career. As Coolsaet and Gillis began chipping away at an Olympic standard, Watson quickly faded into the role of third wheel. He did pacing duty for Coolsaet’s break-out marathon in Toronto in 2010, but he personally struggled, finding that he was not responding to the training.

Watson is a good storyteller. His blog, LeBlogDuRob, might be more celebrated than his actual athletic achievements. His breezy and honest style provides insight into his training, as well as aspects of his personality and life choices that both elevate his ability as a runner and hold him back from greatness. Women, drinking, cookies and pizza are popular subjects.

A recurring theme in Watson’s blog is the term “fade from the front.” These four words explain Watson’s modus operandi. When he was in Grade 11 and struggling to figure out how to run a successful race, his father gave him a simple piece of advice: just go out hard, take the lead and make the others take it back – fade from the front.

Fading from the front has not always been kind to Watson. In his first marathon in Houston in 2011 he faded badly, sputtering across the finish line in a disappointing 2:16:37. It was more than five minutes off an Olympic standard. “I don’t think there’s anybody who would question his ability to put himself in the hurt box,” Scott-Thomas says. “He can run himself almost comatose. If anything, I always wanted him to lay back a little bit and run harder off the back end.”

With the London Olympics looming, Coolsaet, Gillis and Watson all agreed to attack the 2:11:29 standard together at the Toronto Waterfront Marathon. Again, Watson struggled mightily in the latter stages of the race, dropping out and losing an opportunity to be paced to an Olympic berth. Instead, he would have to settle for watching his Speed River training partners both qualify for London.

Sometime after the Toronto Waterfront Marathon, Watson and Scott-Thomas stopped communicating.

“He’s stubborn and I’m stubborn,” Watson concedes. “It wasn’t working for either of us. From my end, I felt I was more of a pace bunny for Reid and Gillis – a workout partner – just a body there to push his two guys.” Watson felt like he was being plugged into a training program that wasn’t designed to work for him. “I was doing workouts based on what Eric and Reid were doing, not based on what I needed,” Watson says.

Watson was struggling and knew he needed to do something about it. Pete was then coaching in North Carolina and invited his brother down to recharge. When Watson told Scott-Thomas that he was heading south, he thought Watson was running away from his problems.“He didn’t support it and he didn’t understand why I was going,” Watson says. “At that point, we had lost a connection with each other.” Scott-Thomas forwarded Watson a training plan, but from Watson’s perspective they were both just maintaining a charade.

Then, Watson did something peculiar. “I don’t know why, but I ran this big 290k week out of nowhere.” Scott-Thomas was furious. “To be honest, I don’t really know what went wrong. I thought everything was fine, until he went to North Carolina. When I called he just said that it was over.”

Within 15 minutes of breaking up with Scott-Thomas, Rob turned to Pete. After years of stepping in and filling the void for his little brother when all else failed, Pete formally became Rob’s coach. They quickly created a road map and targeted a fast spring marathon.

It was an Olympic year, and London was on Watson’s mind. This next race became a make-or-break moment. “You’re living in borderline poverty, running for a payday,” Watson says. “That can be appealing for a little while, but eventually it gets tired. I couldn’t justify the sacrifices much longer and started thinking about moving on from this dream.”

Watson was in search of a flat, fast spring marathon that would potentially have a group of runners going after a 2:10. They quickly focused on Rotterdam, a world-class race where a group of Dutch and German runners would also be chasing an Olympic qualifier. Pete is good friends with American marathoner Shalane Flanagan and her husband Steve Edwards, and he called and asked if they could pull some strings and get Watson into Rotterdam.

The next day, he was on the elite list.

The financial reality of being an elite runner in Canada was also beginning to take its toll. Watson has not been supported by Athletics Canada since 2010, and was getting by doing odd jobs like running a crepe stand, and part-time work. Athletics Canada maintains a point system in order to decide who gets “carded,” meaning the runner will receive $1,500 monthly as well as health coverage. Runners receive points based on how fast they run. “Basically, if I can’t hit the Olympic “A” standard of 2:11:29, I won’t get funding,” Watson says.

Without funding, Watson had to pay for his own ticket and hotel for Rotterdam. “I came up with the cash by using what little savings I had, maxing my credit cards and borrowing money from my parents,” Watson says. “Being 28 years old and having to ask for money from your parents is tough. I’m still paying off that Rotterdam trip.”

On a stereotypically grey Dutch morning, Watson went out with the chase pack that included fellow Canadian and close friend Dylan Wykes. Their group went through the halfway mark in 2:09 pace. It appeared that Watson was again planning on fading from the front.

Watson had a hard time getting at his bottles at the fuelling stations. “Regardless, 25k into the race I was thinking to myself, ‘This feels amazing, I’m going to the Olympics.’” But at 30k he had another problem with the f luid station, and again had to stop to find his bottle. The pack, which was now starting to fray, left Watson to fend for himself.

At 35k he caught his most recent split. “I knew that it was over. I was pretty upset for about a kilometre. I was not going to the Olympics. In that moment, anything over 2:11:29 didn’t matter.” But after a few minutes of feeling sorry for himself, Watson had an emotional epiphany. “I realized that I still was going to run a really good marathon that day so I just dug down and tried to get to the line as soon as possible because I was in so much pain. I realized that, no matter what, I wanted to keep running.”

Watson crossed the finish line and toppled over. “I threw up all over a medic,” Watson says. “I was upset, but when I think about it now, I ended up in a hospital bed on an IV and I couldn’t stop throwing up. What more could I do?” Watson ended up running a 2:13:37.

Watson is aware that he can be his own worst enemy. But his brother is more blunt. “People like to hang out with Robbie,” Pete says, “Everyone thought of Robbie as the life of the party, and that was something that he was embracing as well. If somebody wanted to have a good time and a late night, they could call Rob.” Before Pete agreed to sign on as his brother’s coach he offered Rob an ultimatum: he had to come south and do an intensive, six-week training camp with Pete before every marathon or Pete would not coach him. “He eats all my food,” Pete says laughing. “He comes here to work with zero distractions. It’s about keeping Robbie from being Robbie.”

In the summer of 2012, in an effort to completely remove himself from his bad habits, Watson sold all of his belongings, including his prized possession Dieter, a silver 1997 two-door bmw, and moved to Vancouver. “I didn’t initially think Vancouver was a good spot,” Pete reveals. “We thought he should move down here with us.” But there were visa issues. Watson now does most of his workouts on the Palmer loop in Stanley Park by himself, and works part-time at Forerunners, a running shop owned by Olympian Peter Butler, which also employs Olympic alumni Dylan Wykes and Art Boileau. “I think I may have the slowest PB on the staff,” Watson says.

Soon after the gun went off in Hopkinton, Watson found himself in a strange yet familiar situation. Along with American Jason Hartmann, another overly tall marathoner fighting for his survival in the world of elite running, Watson was leading the Boston Marathon.

They led through 6k. “We knew that the Africans would be coming, so we were fine with where we were,” Watson says. Within a few kilometres, the pack of Kenyans and Ethiopians, including reigning champ Wesley Korir, would swallow up Watson and Hartmann and spit them out the back. The two settled in to run their own races, assuming that would be the last they would see of the lead group. Hartmann was without a sponsor and had stated in the days leading up to the race, that, similar to Watson’s Rotterdam ultimatum to himself, his fate in Boston would decide whether or not he would continue as an elite runner.

At 12k, they kept getting unusual feedback from the cyclist that was taking them through. “The leaders are falling back, currently 45 seconds ahead,” he yelled back to Watson and Hartmann. “Now only 30 seconds.” The two had closed the gap on the lead group and tucked back in again amongst the Africans. “We certainly had a few of the lead guys look back at us in disbelief,” Watson says.

Elbows started to get thrown and heels clipped in the lead group. They weaved all over the roads. “I just decided to get back into my own rhythm,” Watson says. “I wasn’t running my own race, I was running their race.” Watson focused on the road ahead, maintaining his pace. Suddenly, he realized he was all alone out front. He had gapped the pack. “I just told myself ‘Don’t freak out, you’re 40 m ahead in the Boston Marathon, just relax and go with it.’ But it’s the Boston Marathon and there are people lining the streets and everyone is losing their shit. You can’t even hear yourself think. This is the coolest thing ever.” Watson began to wonder if he’d caught a strategic break in the race. “I remember coming up to 24k thinking to myself, ‘If I feel good here I’m going to make a big push. Forget top 10, I’m going to try to win this thing.’”

When he entered the Newton hills, like thousands of runners before him, Watson fell apart. The lead pack, including Hartmann, quickly caught him. They surged, leaving Watson behind. But as with Rotterdam, he was able to put it into perspective. “Even when I got dropped and my legs were shot, I was just enjoying life so much at that point. I loved everything about racing in Boston,” Watson says. He would limp across the finish line in 11th place.

Durability is Watson’s saving grace, and he was back on the track just two weeks after Boston, preparing for his next race, the 10k at Ottawa Race Weekend. He arrived in Ottawa on Friday morning, and went into the elite area of the hotel to check-in with the race. The start lists for each event were posted on the wall. Watson started looking at the prize money involved and who was slotted to compete. He was familiar with how the 10k was broken down and how it would probably play out. But he hadn’t ever bothered to look at any of the details of the marathon. “I knew it was the national championship, but I didn’t know who was on the start list.” Top Canadian got $5,000. There were a couple of guys there that were capable of running 2:20. Watson saw an easy payday.

He went up to his room and called Pete. “I said, ‘If I win this it will pay for my next training camp in Virginia. You won’t have to buy my groceries for me.’” Watson said. Pete was not amused, but figured it was a calculated risk with a relatively high financial reward. “A 2:20 should feel like a long tempo run for Robbie at this point, so I reluctantly gave him the OK.” Watson got off the phone, went back downstairs and he was announced as the marquee Canadian marathoner at the race press conference 20 minutes later.

When the gun went off, Watson immediately sought out his competition, Toronto’s Lucas McAneney, and glued onto him and pacer Thomas Omwenga. At 12k, McAneney was breathing heavily. Watson pounced. “I figured I’d put in a surge for a kilometre and drop him so I wouldn’t have to worry about anything.” Watson made his move, thinking that Omwenga would be obliged to go with him. “I thought that we’d put Lucas in no-man’s-land,” Watson says. But when Watson surged, Omwenga stayed with McAneney. “So, I got stuck by myself.” Watson decided to end it right there, and ran hard for the next 5k, eliminating his competition for good. He crossed the finish line in a controlled 2:18. “I didn’t have to go to the well at all. It was a lot of fun,” Watson said. “I think I’ll go back next year. Maybe I’ll run that same double with Boston in April, who knows.”

After Boston, Rob and Pete began to strategize how they would get Rob under 2:10. He and Dylan Wykes were the only two Canadian men to run a qualifying time for the 2013 world championships in Moscow, but long term injuries ruled out Wykes. Pete didn’t think Rob should sacrifice an opportunity to inch closer to his end goals just to appease Athletics Canada. “Say he opts to run Worlds – he’s not going to medal at worlds, let’s be honest. According to the way things are now, even if he runs a 2:12 in Moscow it won’t get Robbie carded. He’s 30 years old. Now he has to go back to work at a shoe store.” Shortly after Boston, Watson announced on his blog that he would not be running in Moscow and would instead pursue a fast fall marathon, with the end goal being Rio in 2016.

An unlikely person from Watson’s past stepped in. “When I became the endurance co-ordinator with Athletics Canada, Rob was one of the first people I reached out to,” Dave Scott-Thomas says. Watson and Scott-Thomas had several phone and email exchanges, which led to Watson’s change of heart about running in Moscow. When asked about whether or not Watson was promised carding in exchange for running Worlds, both were coy. “Carding is in a state of f lux,” Scott-Thomas says.

Watson will run for place in Moscow, and then for time at a fast fall marathon. He cites his heroes Steve Jones, Rob de Castella and Carlos Lopez, who all ran in the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics and then battled for the world record two months later at the Chicago Marathon.

In order to accomplish all of this, Watson claims his days of debauchery are over. “I’m not going out and staying up until five in the morning anymore.” Watson says people are now complaining that his blog is no longer exciting or funny. “If I run a 2:09 marathon, I’ll be content with writing boring blog posts about working hard and running fast.”