This story first appeared in the print edition of Canadian Running back in 2009.

It’s a bitterly cold December afternoon, not a runner in sight, when a man limps into the Lucky Dice restaurant on Toronto’s Lakeshore Boulevard. He nods hello to a couple of elderly guys sipping beer at separate tables. The waitress greets him by name and offers a “double double,” which he graciously accepts before sitting down at our table. Jerome Drayton is 10 minutes early.

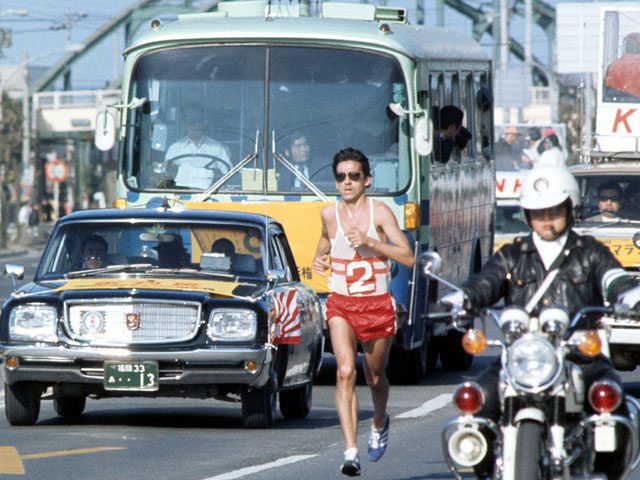

Looking at his dishevelled appearance–grey brush cut, a bulging midriff beneath a khaki jacket that offers inadequate protection from the cold, and a pair of trainers with no distinguishing logos–the man now sitting across from me bears no resemblance whatsoever to the man who won Japan’s Fukuoka International Marathon three times and who was once the No. 1-ranked marathoner in the world. Throughout the 60s and 70s, Fukuoka organizers handpicked the world’s elite, earning the race a reputation as the unofficial world championship. The time Drayton recorded in 1975 in his second victory there – 2:10:08 – remains the Canadian record to this day. After 34 years, it’s never been threatened. Drayton has always been ahead of his time.

“I’ve got osteoarthritis,” he offers as an explanation for his limp. “It’s nothing to do with running, by the way.” After he retired from competition, Drayton says he was running five miles a day, but in the winter he didn’t want to go out in the cold, so he got hold of a stationary bike. “I took it back to my apartment and put the resistance on it. I fell down the next day and went to the hospital and they said, ‘You have a hole in your knee.’ I threw that bike away. I lived on the 19th floor. I put it down the garbage chute in pieces. It made a hell of a racket.”

Drayton laughs aloud at the memory. Now 64 years old, he has no shortage of memories and many of them, the ones he willingly shares, have something to do with running. Along with the three Fukuoka victories, he also underscored his greatness by winning the Boston Marathon in 1977 after several attempts. This victory may well resonate with Canadians as almost everyone who has taken up running has heard of Boston. For Drayton though Boston invokes memories of his verbal battle with then-race director Jock Semple over the lack of water along the route. It landed him, well, in hot water.

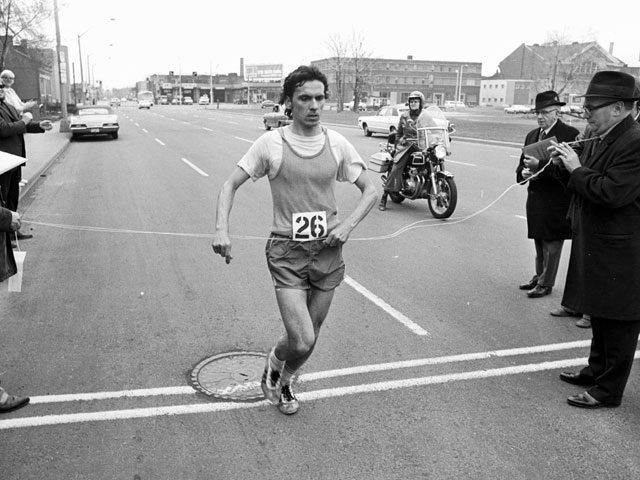

“Bill Rodgers and I broke the pack at around 10 miles. Nobody followed us,” Drayton recalls. “Bill was from Boston and he had a lot of friends dash out and give him a personal drink. I said ‘Bill, don’t they have any water stations along the route?’ He shared his drink with me, but after a while, I said no. The irony is, he is the one who dropped out at Heartbreak Hill. I was alone. It was getting hotter and hotter. I thought a couple of times I was going to drop dead. After I crossed the finish there was a water fountain and I just soaked myself in the water. Then when it came time to get the awards I said to Jock Semple – he’s a real nice guy – ‘Did it ever occur to you to have water stations?’”

At this point in the story, Drayton is laughing aloud, clearly enjoying himself. “He got angry and started to deny, deny. He should have worked in the government. He said ‘Who do you think you are, an Olympian?’ ‘This is the 1970s,’ I said. ‘You have 3,000 runners out there and no water.’ He still refused to accept it.”

As the defending champion he was invited back the following year and bumped into Semple as he tried to enter an area restricted to vips. Drayton was only trying to use the washroom before the start. Semple blocked his path and pointed to the portable toilets where a long lineup had formed. “I had my sunglasses on and a real tattered warmup suit, which I was going to leave on the side of the road,” Drayton recalls. “He put his hand on my shoulder and said ‘Hold it son, you can’t come in here.” I said, ‘Don’t you remember me?’ I took off my sunglasses. ‘How about now?’ I opened up my tracksuit and showed him my Maple Leaf and he said, in his Scottish accent, ‘Oh it’s you. You give me trouble.’”

The memories are rich and joyful, but in those days the athletes didn’t profit financially from any glory. This was before professionalism existed, a time when runners were thought to be more than a little eccentric. Drayton certainly epitomized the prevalent loneliness-of the- long-distance-runner mentality. There was no massage therapy following a hard training session. He would take a hot bath. There was no prize money, no appearance money, so he worked 35 hours a week at the Ontario Ministry of Culture and Recreation. Asked if he had regrets that he didn’t earn money from the sport, Drayton shakes his head. “No, not at all. You can’t miss something you never had before,” he says. “It was a serious hobby. Obviously, I enjoyed it. I enjoyed the travelling. I had to work at the same time. So I had to do my workouts before nine o’clock and after five.”

Drayton says he pushed his training up to 190 miles [300k] a week after hearing that four-time Olympic champion Lasse Viren, a 10,000m specialist, was hitting 210 miles [336k] a week. “Of course he wasn’t working at the time, so he could run three times a day,” Drayton says. “I started off slowly, working up to 190. It became uncomfortable mentally after 140 miles a week because of the work situation. I sat at a computer at work. I had done 10 miles in the morning. I kept sitting there thinking ‘Oh God, I have to do another 18 miles tonight.’ Saturdays and Sundays I looked forward to because you got an extra eight hours of personal life.”

Drayton always had a reputation for being reclusive. Though he is invited to the annual reunion of his former club, the Toronto Olympic Club, he rarely turns up. And he was a no-show when Athletics Ontario inducted him into their Hall of Fame last November, though he had the courtesy to write a letter explaining his arthritis had been acting up terribly.

Back when he was running with the club, they would meet for Sunday morning runs, with Drayton often setting off by himself. If he did run with someone, he would rarely utter a word. Drayton’s rough childhood may explain some of this peculiar behaviour. He was born Peter Buniak, on January 10, 1945, in Munich, Germany, to parents of Russian-Ukrainian background. The Second World War was coming to an end and extreme poverty was widespread. Drayton says his parents had travelled to Germany from Poland aboard a cattle train.

“They actually spent time in concentration camps, not because they were Jewish but because they had tuberculosis,” Drayton says. “My parents had to work, but they couldn’t keep me at home. I spent four years at a group home. Not speaking German, I got in a lot of fights. The rest of the kids were all German. It wasn’t a good time.”

Drayton’s parents eventually divorced and his mother, who had custody of him, moved to Canada and then brought Drayton over to Toronto in November, 1956, when he was 11. “My isolation, or spending most of the time alone, was probably due to my background,” Drayton says. “I was in a group home, but I did not feel part of a group because I was not German. Also, I was a single child – solitude, being alone, but not lonely.”

Drayton remembers being called “DP” when he arrived in Canada. When he asked the kids what these taunts meant, he was told he was a “displaced person.” Again he had a hard time fitting in. When he took up running in high school, Drayton’s singlemindedness quickly became evident and it wasn’t long before he won top-calibre events. After winning the Ontario high school championships for Mimico High School, he was recruited to the Toronto Olympic Club, where he began working with national distance running coach Paul Poce. While Drayton credits Poce and his clubmates for much of his success, it’s his mother, Sonia, who has remained at the centre of his life. Her struggles to raise him are the stuff of great fiction, but sadly it’s all true. Drayton lives with Sonia, now 85, in a west Toronto neighbourhood and looks after her.

Over the years, Drayton earned respect for his legendary front-running and always gave a good account of himself. In an era before the road racing explosion and before the sport was dominated by East African runners, the best racers regularly encountered each other at the major races. Drayton took on everyone, including American Frank Shorter, the 1972 Olympic marathon champion and winner of four Fukuoka titles.

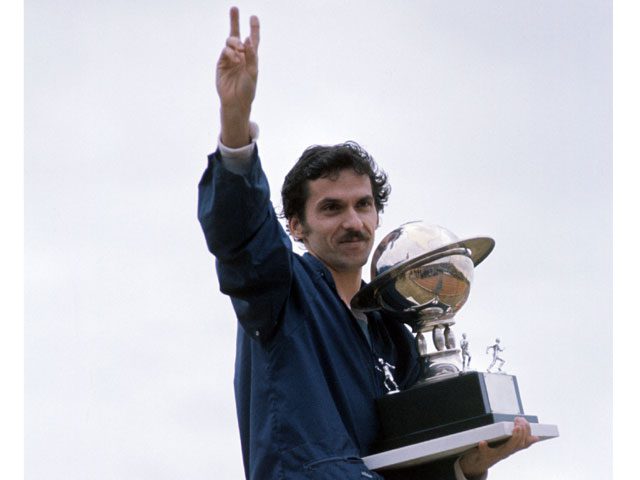

“I always loved running against Jerome because you always had to be ready. You always had to be tough,” Shorter says. “But the advantage I felt I had over him was I was faster. I felt that if I was close to him near the end, I was OK. That worked, except at Springbank that one year when he got away and beat me.” The Springbank International Road Races were held in London, Ont. and were once one of the most prestigious events on the North American road racing circuit. During the 1975 edition of the 12-miler, Drayton and Shorter broke away early from Bill Rodgers and Commonwealth Games marathon champion Ian Thompson of Britain, then waged a memorable tussle over the final 5k. Drayton eventually won in a time of 54:52, 10 seconds ahead of the American.

“You know, I can remember sitting down and drinking a few beers with him. In fact, I remember the beer was Labatt’s,” Shorter remembers with a laugh. “It was very amicable. The good athletes, particularly in endurance sports, can turn it on and turn it off. They turn the switch off when they are not competing. Jerome could do that. I had no trouble socializing with him because I am the same way. Don’t confuse his being reclusive with his not being social.”

Because of his 1975 Fukuoka victory, Drayton was one of the favourites to win the 1976 Olympic marathon the following summer. And since the event was held in Montreal, there was additional attention that the reclusive runner could do without. East Germany’s Waldemar Cierpinski took the gold ahead of Shorter, while Drayton wound up sixth behind Lasse Viren, who had earlier pulled off the 5000m/10,000m double for the second time at an Olympics.

The disappointment was evident in the media and among those who followed Drayton’s progress. But what they didn’t know was that he had caught a cold in the days preceding the marathon. “There was some pressure on me, but I still ended up with a cold,” Drayton says. “I was probably lucky that the Ethiopians and Kenyans ended up boycotting the Olympics. I am thinking I am lucky to have come in sixth. If the Africans had been there, I might have been 26th. I got a measure of satisfaction because I was invited back to Fukuoka as the defending champion. I was hoping Cierpinski, the 1976 Olympic champion, would also get invited and he was. I had some small satisfaction in winning for the third time.”

Despite his enormous commitment to training, Drayton counted several runners from the Toronto Olympic Club as friends. Because they were scattered across Toronto, they socialized after races or after the occasional training session. The coach, Paul Poce, was probably as close as anybody; he was the best man when Drayton got married (and not long after, divorced). Poce remembers when Drayton approached him and revealed he had legally changed his name. The explanation he gave was that he didn’t want any link to the Buniak family. His father had disappeared when he was very young. Like many of the Toronto Olympic Club members, Poce told him he would always be “Pete” to him.

Poce claims Drayton was always a student of the sport, borrowing ideas from anyone he deemed successful. There was a time when they were at a training camp in France. From their dormitory window they could see Mohamed Gamoudi, the 1968 Olympic 5,000m champion from Tunisia, working out. “It was just pelting rain,” Poce says, “and Gamoudi was there running 400s. He would run 400, jog a 100, and was doing these in 61, 62 seconds. Drayton said: ‘Wow, he did 14 or 15.’ We lost count. Next thing, we came home and we were at Toronto’s Varsity Stadium and Drayton said: ‘How would you like to time me in some 400s?’ He ran them all in 61 – the same as Gamoudi.”

Poce can also remember driving a car ahead of Drayton during Detroit’s Motor City Marathon in 1969, a race in which Drayton broke the Canadian record at the time, with a 2:12:00, and finished 15 minutes ahead of the second-place finisher. Leading by 800m midway through the race, Drayton seemed to be losing concentration, so he called out to Poce. “I am pacing him in a car,” Poce recalls, laughing, “and he said ‘Put the radio on such and such station’ and all of a sudden this heavy rock came on. I could feel the pace pick up immediately. He was all by himself and he was getting ragged. As soon as he heard the music, he was energized.”

An hour has passed and it’s now dark outside the Lucky Dice. Drayton declines an offer to be driven home. He’s going for a beer at the bar next door. I ask if the locals know he was a runner of world renown. Drayton says the bar owner hung a photograph of him on the wall. Another bar across the street also hung a picture, but it’s now a strip club and Drayton hasn’t been inside for a year. These are small acknowledgements of his incredible athletic past.

“I don’t miss it,’ Drayton says, before shaking hands. “It’s a fickle sport. You can get injured overnight. I don’t know how long people last on average – maybe 10 years. I would say go to school, get a degree and if you can get a part time job, you have something to fall back on. I have my pension. I am happy now.”

Paul Gains is a freelance writer based in Cambridge, Ont.