Blind runner Rhonda-Marie Avery: Death to the left!

By David Carroll

By David Carroll

Rhonda-Marie Avery claims she was completely sober when she decided to run the Bruce Trail from end to end. It was August 2012, and she was drinking a cup of tea when she heard a news story about Cody Gillies of Orangeville, Ont. Gillies had just set a new world record, running the 885-kilometre trail in 12.5 days.

And Rhonda-Marie thought to herself, ‘yeah so?’

“I mean, he was 20-nothing,” she says. “He was young and fit, no disabilities, a firefighter. Of course he’s going to set a new world record. What’s so impressive about that?”

As she drank that cup of tea, Avery decided to do the firefighter one better. Not only would she run the trail from end-to-end, she’d do it with only 8 per cent vision.

Avery was born with a rare genetic eye disorder called achromatopsia, which means she has no cones in her retina.

“She sees better in the dark than in the light,” says Don Kuzenko, who, for 20 days this past August, served as Avery’s personal chef, driver, physician, psychia- trist, life coach and head cheerleader.

“You know how well you can see in the dark?” Kuzenko explains. “That’s what Rhonda- Marie can see, which obviously isn’t much. In the daylight her vision is even worse. Imagine a floodlight shining in your eyes on the morning of a bad hangover. All you can see are bleary blobs and shapes.”

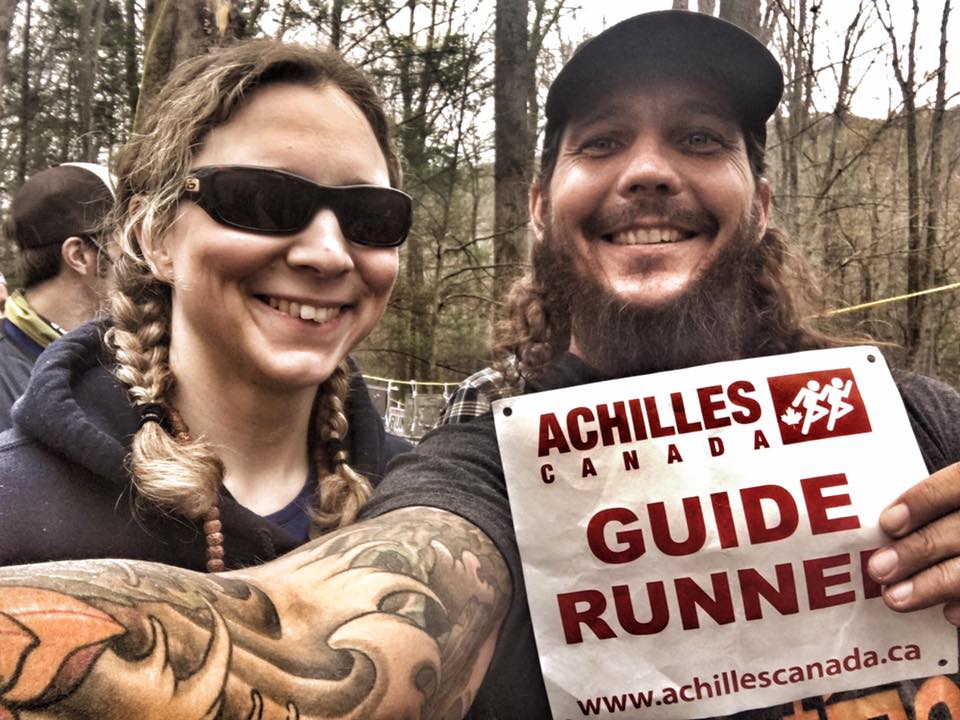

Five years ago, when Avery was first getting into running, she met with a group called Achilles Canada. Achilles paired her up with guide runners, and taught her how to run safely. Now Avery wanted to return the favour. This end-to-end run was all about raising awareness for Achilles.

“Achilles was hugely important for me,” Avery says. “Not only did they teach me how to run, they also helped break down my barriers of fear. For a blind person, just crossing the Walmart parking lot can be the scariest thing in the world. I actually still think that’s scarier than running the Bruce Trail.”

Most people, on hearing that a legally blind person is running the Bruce Trail, are baffled. How is such a thing possible? The footpath meanders up and down the edge of the Niagara Escarpment, which is essentially a 400-million-year- old coral reef. Even fully-sighted people, travelling at walking pace, can easily twist an ankle on its pitted rocks.

Then there are the rattlesnakes. And the 100-metre crevasses.

To offset the risk, Avery enlisted 50 volunteers from the ultrarunning commu- nity (a minimum of two people per day for each of the 20 days) to help guide her on her run. Some she’d run with before; some not. All were given a quick tutorial on how to guide.

“Running with me is kind of like pacing a zombie for the last 25k of a 100-mile race,” Avery joked. “Plus, you have to point out all the highlights underfoot.”

Because of the complex nature of the Bruce Trail terrain, a special lexicon was developed. A typical guide, running one-and-a-half metres ahead of Avery, usually sounded something like this: “Rock. Root. Rock right. Rock salad. Toe grabber. Ankle-grabber. Limb-eater to the left. OK, take three steps up. Now two steps down onto flat soil. Thread the needle! Dinosaur steps!”

This language grew more colourful as the days progressed. Muddy trail became known as “mashed potatoes.” “Scalloped potatoes” meant mud with rocks and roots thrown in. A “chicken head” was a root sticking straight up. “Cheese Grater” was a pile of pitted limestone. When the trail opened up and became smooth enough for running that was called “butterscotch pudding.”

The most important phrase of all was “death to the left!” That got used whenever oblivion came within inches of the trail.

When asked how she was able to trust the guides – many of whom she’d never met before – Avery is philosophical. “I had no choice,” she says. “If I want to lead this kind of life, I have to trust that people will watch out for me. I’ve done triathlons and I’ve had to tether myself to swimmers I’d never met before.

Were they proficient in the water? I had no idea. But if I wanted to do that race, I had no choice.”

Before setting out on her Bruce Trail run, Avery sent an email out to her guides, which contained the following rules:

1. Always come to a complete stop before turning around to see how badly I have fallen. I will fall. It is not your fault.

2. There is no such things as bears and snakes. I seriously don’t want to know. Ignorance is bliss.

3. Don’t coddle. Disability means many things. A justification for excuses is not one of them.

By the evening of the sixth day, Avery had covered 300k of trail. The Envisions team (as Avery’s entourage became known) was billeted somewhere near the Beaver Valley. Rancid-smelling trail shoes littered the mudroom. The laundry room was a sea of toxic waste.

For the first time on the tour, the whole crew (Avery, Kuzenko, a documentary film unit, the next day’s guides, assorted family and friends) all ate together. There was a mountain of food: 10 pounds of lasagna, veggie burgers, spring rolls, garlic bread, a colossal salad. For dessert, vanilla ice cream was scooped into bowls. Avery added WowButter and pumpkin seeds to hers.

“Day six!” she cried. “I’ll take Crazy Personal Goals for 600, Alex. What’s 900k long and two feet wide and can make a grown woman cry? Oh yeah, that’s right, the Bruce Trail!”

She had some swelling in her knee, but her spirit was high. She kvetched about the trail detour that had added 4k (and 90 minutes) to the day’s run.

“Look at it this way,” said Cody Gillies, the aforementioned record holder who gamely volunteered to mentor and guide Avery for five days of her run, “the Bruce Trail is now 889k long, not 885 like when I ran it. So 14 days from now, when you finish this thing, you’ll own the new record for the fastest end-to-end trip, on the longer trail.”

It was a generous thing to say, considering the record she’d be eclipsing was his own. But Avery wanted no part of it. “You can keep your title,” she said. “I’d rather have the extra 90 minutes sleep.”

By Day 14 the Envisions team had encountered one bear, dozens of snakes, 90 stile-crossings, a week of cold wet weather and an endless parade of “death to the left!” Still, the biggest challenge wasn’t the blisters or the wildlife. The biggest challenge was lack of sleep. Avery had been running the equivalent of a marathon every day for two weeks. Due to the cragginess of the trail, however, those runs typically lasted 12–13 hours. Add in meal breaks, travel time to and from the trail-heads, stretching, planning the next day’s route and meetings with the next day’s guides, and Avery was left with only four or five hours of sleep per night.

“She’s doing very well,” Don Kuzenko said, with the entourage settled in at Georgetown. “There were a couple of road sections today, so she made good time there. Plus, her body is over the initial shock. It’s hardening up.”

Avery agreed with this assessment. “Last week was brutal,” she said. “We had a lot of rain, a lot of cold weather. I’d have knee pain, then stomach pain, then some other pain. But after Day 10, things turned around. There was no localized pain anymore. I still hurt, but it was a more general pain. After that, the real challenge became mental exhaustion.”

Staying alert was essential. Avery not only had to run for 12 hours every day, she needed to pay attention to the steady stream of information being relayed by her guides. “Sometimes I got so bored of hearing them say ‘rock, root, rock, root,’ I’d ask my guide to tell me stories instead,” she explained. “It was easier to pay atten- tion to stories, plus I could hear how their voice reverberated off the ground. Usually I can tell if the ground is rocky or covered in roots, just from the echo of their voice.”

I ran with Avery on Day 18. She’d covered 780k by that point, and her running had slowed to a shuffle. Somewhere between Hamilton and Grimsby, she sprained her ankle. She didn’t yelp or cry out. I didn’t even know it had happened.

I ran with Avery on Day 18. She’d covered 780k by that point, and her running had slowed to a shuffle. Somewhere between Hamilton and Grimsby, she sprained her ankle. She didn’t yelp or cry out. I didn’t even know it had happened.

“We’re going up a hill,” I said, inadvertently breaking one of the cardinal rules. Guides weren’t supposed to mention hills. They were to be referred to as “inverse declines.” Or “mounds of opportunity.”

Regardless, Avery didn’t respond. She slumped to the ground at the foot of the scarp face.

“That was a bad moment,” Avery explains, later. “But I’d had lots of bad moments already. There were so many times I thought to myself, ‘I can’t do this, I’m not capable.’ I thought, ‘Kilian Jornet could do this, but not me.’ I felt guilty that I wasn’t able to run the whole trail; I beat myself up for having to shuffle and walk part of the time. But then I realized, even a disabled person brings a skill set. I just have a different starting point from a fully-sighted person, that’s all. It’s no better or worse; it’s just different.”

This acknowledgment – that disability is a limitation, but not necessarily a dead end – lies at the heart of Avery’s message. “Once you accept your differences and make peace with them,” Avery says, “you can develop strategies to succeed, no matter who you are. But acceptance isn’t an easy road. It’s a crappy trail full of rocks and roots. It’s tougher than the Bruce.”

Early the next morning, on Day 19, Rhonda-Marie Avery posted this on Facebook: “Waking up in spasms of pain from a sprained ankle yesterday. Trying to be still. Today I will hobble, walk, shuffle towards the finish. But nevertheless, today I will move. Relentless forward movement. And a single hope of not disappointing the world, hangs in the air.”

Thirteen hours later, another update came in: “Day 19. 53.6k done. Back on track.”

At 1:30 p.m. on Saturday, Aug. 23, Rhonda-Marie Avery sprinted across a grassy field at Queenston Heights. Dozens of people jogged in her wake: friends, family, guide runners, others with disabilities. When Avery reached the stone cairn that marks the southern terminus of the Bruce Trail, she grabbed her son Izaak and lifted him in the air. Izaak’s siblings, Xavier and Terese, helped prop their mother up.

The crowd cheered and took pictures. There were tears, speeches and Advil. A Bruce Trail representative presented Avery with an end-to-end badge. The sun streamed through the trees and danced in blobs on the ground. Speckled sunlight. For Avery, that’s the worst possible kind.

“There’s a lot of stuff I can’t do on my own,” Avery said. “If I want to go running, I need to ask somebody to run with me. If I want to run on the Bruce Trail, I need to find someone who can drive me to the Bruce Trail and then run with me.”

She ate an apricot and glanced around at the crowd of people. Cody Gillies was there, helping cut a giant cake. Dozens of ultrarunners milled about, trading stories of their latest 100-mile races.

“There are a lot of downsides to having a disability,” Avery concluded. “But one of the positives is I’ll always be surrounded by community.”