This feature originally appeared in the January/February 2017 issue of Canadian Running when we awarded Ed Whitlock the 2016 Canadian runner of the year award. Whitlock passed away, on March 13, 2017, a few months after this story was published.

For 32 years Milton, Ont. has been the home of the man who continues to defy what is possible for runners considered past their athletic prime. Whitlock’s house only has subtle signs of a runner’s residence. A basket of trainers at the entrance. Plaques, dating back to the 1990s, including that of the Columbus Marathon, where he ran 2:51 and 2:52 at ages 68 and 69, decorate the ledge above his kitchen doorway. There are print clippings of Whitlock’s most recent world record on the dining room table attached with a paper clip. On top, a full-page spread of the Globe and Mail’s sports section from the day after his Oct. 16 marathon in Toronto featuring Whitlock’s mercurial grin after crossing the finish line.

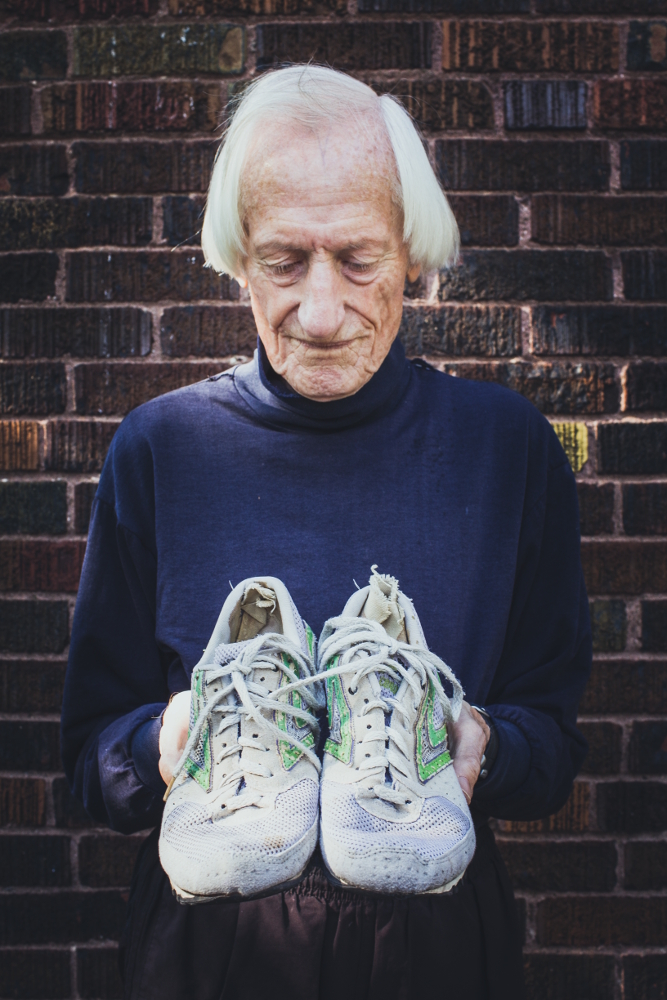

Next to the table is an antique dresser with various trophies throughout the years, including one attention-grabbing Canada Running Series trophy topped with an actual Coors Light can. “Still full, too,” Whitlock says. The trophies sit on an antique dresser filled with memorabilia that would make a running historian excited. In one box are more than two dozen medals, many of which read “South London Harriers,” from his U.K. grammar school days, next to a childhood photo more than six decades old. Growing up in London, he was one of the city’s top talents defeating the likes of future Olympic silver medallist Gordon Pirie. He’s dressed in running attire, shorts over long tights, a long sleeve and a pair of pristine trainers that must be at least 15 years old. Ed Whitlock seems ready to run at any moment.

CR visits Ed Whitlock

“I would have liked to run in the Olympics but that’s water under the bridge,” Whitlock says. Injuries, including a bad Achilles, and improper training in his early years derailed his running aspirations for the most part – except for a four- or five-miler in Toronto’s High Park when he was 25 and in town for a teaching job – until his 40s. “I was appalled at how I ran,” he recalls. “I decided it was so ridiculous that I wasn’t going to do it again.

“If I had continued running and properly trained when I was young, I probably wouldn’t be running today,” the 85-year-old says. “In that sense, I don’t regret missing out on any opportunities.”

Whitlock’s latest feat? A 3:56 at the Toronto Waterfront Marathon in October, improving the previous world record by more than 30 minutes. He did it despite less-than-ideal training and thought it would be a “disaster” at the halfway point of the race. If a “disaster” entails only breaking the record by 30 minutes, it’s tough to imagine what Whitlock would have run if the lead up was ideal. He averaged 5:36 per kilometre for 42.2k, a performance which has kept him busy in the weeks following the race as he has made appearances on a number of international media outlets.

The octogenarian, who turns 86 in March, admits that, “I type my name into Google on occasion,” though his recent marathon run did not require any sort of initiative on his part to raise his profile. “I don’t have a personal Facebook,” he says. “I don’t even have a cellphone.”

The Canadian, who some call “a national treasure,” holds so many age-group world records that he can’t pinpoint the exact number. According to the Association of Road Racing Statisticians, he owns more than 25 age-group world records in road racing, from the 5K to the marathon. And he holds many more on the track.

Whitlock moved to northern Ontario after university to pursue a career as a mining engineer. He would later meet his wife, Brenda, who is also from England, over afternoon tea through a connection with mutual friends in Toronto. The two have been married 58 years. Before moving to Milton from Montreal, where he spent 20 years, Whitlock had stays in Guelph, Ont., Woodstock, Ont. and Toronto.

He returned to running in his early 40s at the urging of his wife. He then ran his first marathon with his son Clive. The 5’7″ figure who now only barely crests 100 lb. ran a 2:31 marathon before he was 50 and didn’t slow much over the next 20 years. As he moved into older age groups, records began to fall. Now, he is recognized by runners around the world, in part due to his fast running and signature white hair.

One of the most-documented aspects of Whitlock is his ritual of training in a cemetery, conveniently located minutes from the home he has lived in for more than 30 years. “I haven’t always run in the cemetery,” he explains. “When I first moved here in 1984, I ran around town. Lots of roads to cross, never knowing whether traffic will wait for a while, so I began doing out-and-back runs on the escarpment. I was apprehensive because it was a long way home if pains and aches came up.” It was 15–20 years before Whitlock transitioned to training at Evergreen Cemetery. “Everyday around 2–3 p.m.,” one groundskeeper says when he’s asked about Whitlock’s daily routine. The 250 m trip to the cemetery from Whitlock’s nine-decade-old red brick home involves two almost-immediate right turns from his doorstep. It’s a straight shot from there as one can stare through the gates and see Whitlock run into the distance.

In the winter, he can spot the icy areas and avoid the wind. In the summer, the cemetery is dappled in shade, as Whitlock explains. “There’s not much variety, it’s boring running around and around but, somehow, I’ve gotten used to it. I don’t count the laps and don’t time the laps so I don’t get into competitions with myself.” Whitlock’s training is done almost exclusively alone. “If you run with someone else, you need to run at their pace or they need to run at my pace,” he explains. “Alone, I can run how I feel.”

In 2003, he became the first person over 70 to break 3:00 in the marathon, a 2:59 in Toronto, on the same day the men’s open world record was set in Berlin. One year later, he produced his “best race ever,” as he describes it, with a 2:54 marathon at 73. He made global headlines, though social media as we know it today – Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and YouTube – did not exist. Whitlock thinks the 2:54 marathon at 73 would have made greater ripples today than it did in 2004. “Sub-3:00 at 70 has a greater resonance than sub-4:00 at 85. Sub-4:00 at 90 would be different, 85 is an odd age.”

Whitlock was quick to shut down the foreshadowing of a sub-4:00 at 90.

“I don’t think sub-4:00 at 90 is probable,” he explains. “Based on what I think I might do, with ideal preparation, there might be a one-to-two per cent chance of doing that. But a marathon at 90 is too far in the future to have an ambition. To an extent, I tend to focus on shorter term objectives.”

Whitlock does not have current race plans for the future. (Editor’s note: Whitlock ran a 15K world record weeks after CR visited him in Milton.) Rather, he will be returning to London for the first time in five years in December to visit his sister. “I don’t like flying,” he admits. “I don’t mind it much when in the sky but I don’t like airports – bad places.”

For a man that arguably puts more kilometres on his legs than he does his car – the couple’s 20-year-old Buick has 120,000K – Whitlock continues to drive daily. “We also have a new Mazda out there,” Whitlock says pointing to the white vehicle in the couple’s spacious driveway. “I’ve only become marginally proficient driving it.”

In 2016, Whitlock has run age group world records in the marathon, half-marathon, 15K (just one month after setting the marathon record), 10,000m, 5,000m, the mile as well as the indoor 3,000m and 1,500m. Many of his performances, if age-graded, would put him near the top of the world rankings on an annual basis, if not threaten the open world records. “No, I can’t say that,” Whitlock replies when asked whether he’s one of the best-ever Canadian runners. “I am one of the greatest runners at my age.”

Ed Whitlock’s marathon records (over 70)

Men’s 70–74 world record

2:54:48 (4:08/km pace)

Age-graded time: 2:03:57

Men’s 75–79 world record

3:04:54 (4:23/km pace)

Age-graded time: 2:07:15

Men’s 80–84 world record

3:15:54 (4:38/km pace)

Age-graded time: 2:02:10

Men’s 85–89 world record

3:56:33 (5:36/km pace)

Age-graded time: 2:08:57

No secrets

“I think genes are 80–90 per cent responsible,” he says. “I suppose longevity genes enable me to keep going. I’ve been able to overcome my injuries and have never had any serious setbacks. There’s a degree of perseverance but that may well be genetic, too.” Whitlock’s father lived to 82, his mother 95 and he notes a relative living to 106. Whitlock has two sons, Neil and Clive, both in their 50s, with his eldest still competing. Whitlock and Brenda have no grandchildren.

Whitlock recalls three times overcoming what was believed to be serious knee injuries that forced him to take time off for at least one year at a time. Whitlock describes one episode where he was told that he has serious osteoarthritis and nothing could be done. A second opinion, however, from Toronto specialist (and runner) Mark Bayley, suggested that nothing was too bad. “I was able to gradually run it off and after that, I felt better,” Whitlock recalls.

Training-wise, Whitlock is transparent with details, albeit his methods are quite simple: just run, a lot. His training runs reach as long as three-and-a-half hours in the cemetery around a 500 m loop. No water, even on the hottest days. (He ran the men’s 85–89 10,000m world record in 35 C under a heat warning in Toronto last summer.) Perhaps, the most glaring difference between Whitlock and the average runner are his shoes.

85-year-old Ed Whitlock runs sub-4:00 marathon, shatters WR

On Oct. 16, Whitlock raced with a pair of 20-year-old Brooks, one of many identical versions, though all in varying stages of disrepair, he has in his home. To give the shoe a Whitlock makeover, he removes the rubber sole, cuts out the majority of the cushioning on the heel, and reattaches the grip in a sort of running shoe surgery. “All the newer shoes seem too stiff,” he explains as he folds his pair of Brooks flats in half like he would a piece of paper. At the Scotiabank Toronto Waterfront Marathon expo, he brought his favourite pair to the Brooks booth and asked, “why can’t you make them like this anymore?” He still owns a “brand new” pair of the Brooks shoes, still pristine white decades later.

He also follows no specific diet. “I just eat what I want,” he says. “I’m not a vegetarian, but I don’t eat a lot of meat.” He admits that he consumes more sugar, mostly in the form of peppermints and ice cream, and fat than a dietician would recommend. He drinks less than a dozen beers a year, mostly on special occasions, but has wine at dinner.

One of the world’s most famous masters runners has never run the world’s most prestigious marathon. Though he has done about 40–42 marathons (he’s not sure exactly how many), averaging about one per year since his debut, Whitlock has never run Boston.

“It’s not record legal,” he says, alluding to the race’s point-to-point course and net downhill profile. “I would like to run Boston because it is the marathon and I’m sure the atmosphere is great. But it would not be a good course for me as there are hills. I also don’t like running one-way races. At the end you have to assess how well you have done and apply any adjustments – wind, course and elevation – to explain away your performance. All those things even out in a race that starts and finishes at the same place.”

On the topic of races, Whitlock says that he followed the Rio Olympics last summer. He has no favourites, saying “I don’t have heroes in my life,” and that “I don’t believe I should be a hero.” He says that “the most exasperating event is the 1,500m. That’s ridiculous the way they run that race now,” referring to a really slow first three laps followed by a fast final 300 m.

Whitlock often receives questions about training and what he advises other people do. “I’m not sure what I’m doing is good for me, let alone anyone else,” he says. “In general, people should find what’s best for them and go according to that.”

His records would suggest his methods are doing him just fine.