Racer dies at Ultra Fiord 100-mile race, Patagonia, Chile

By Jacqueline Windh

By Jacqueline Windh

A racer died last weekend while competing in an ultramarathon in southern Patagonia, Chile. Mexican runner Arturo Martínez Rueda was competing in the 100-mile Ultrafiord race when he succumbed to apparent hypothermia at the highest part of the route.

Patagonia is a tough part of the world to plan a race. The tip of South America juts more than 1,000 kilometres farther southward, towards Antarctica, than any other continental land mass. The winds swirling around that southern continent make trees grow on a slant here. The tree-line sits around 500m. Snow can fall at any time of the year–especially in the mountains.

I ran the inaugural edition of Ultrafiord last year. The terrain was even tougher than I had expected. Most racers, at least of those who finished, took 50 per cent longer on course than planned. (This is significant on a remote ultra, because it affects what you carry with you as far as food, clothing, and spare headlamp batteries). My time of 19 hours for the 70K distance was good enough to place me in the top half of the field. Several of the 100-mile racers took over 40 hours.

However, last year, we were blessed with unusually good weather: nearly windless, even on the mountaintop, with temperatures just below freezing.

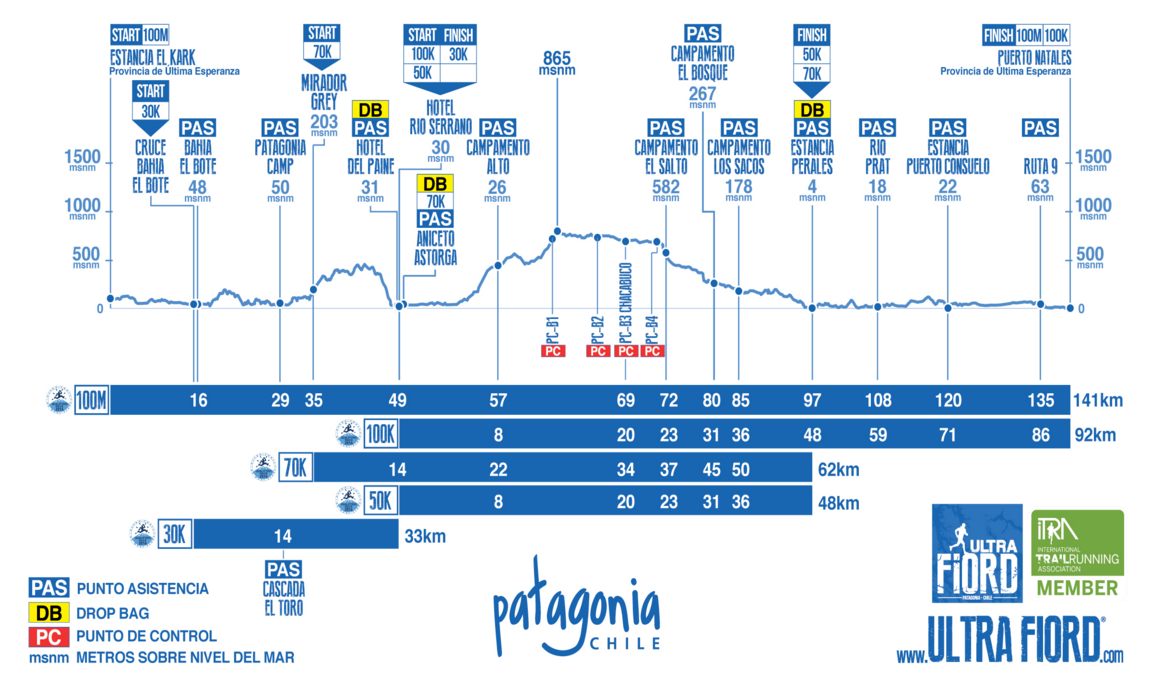

This year, with a more typical Patagonian weather forecast calling for strong winds and snow, race director Stjepan Pavicic shortened the routes (Ultrafiord offers simultaneous races of 100 miles, 100K, 70K and 50K), and diverted them so the maximum elevation attained would be 850m rather than the originally planned 1,240m–still well above the tree-line.

This year, with a more typical Patagonian weather forecast calling for strong winds and snow, race director Stjepan Pavicic shortened the routes (Ultrafiord offers simultaneous races of 100 miles, 100K, 70K and 50K), and diverted them so the maximum elevation attained would be 850m rather than the originally planned 1,240m–still well above the tree-line.

Martínez Rueda was last seen alive by racers who passed him at the highest point on the route. It was snowing, and the wind was described as “fierce.”Martínez Rueda was seated on a rock, dressed in running shorts, with his head bare. His location was between two checkpoints a mere 5K apart (although five extremely challenging kilometres). At the moment, it is unclear what information the racers who passed him gave to checkpoint personnel, and why race personnel did not go to his assistance.

Another hypothermic racer survived thanks to the aid of two Argentinian racers. They reported on Facebook that they helped her to an aid station, at a cost to their own race times. “She wanted to sit down, if we hadn’t helped her she would have been another victim.”

As would be expected, controversy is swirling online about the race organization and their safety protocols. Numerous racers expressed concerns about safety last year, including me. Last year, at least one racer affected by hypothermia who otherwise might have died was given assistance by other racers: Nikki Kimball and Kerrie Bruxvoort found him seated beside the trail and helped him to the next aid station, moving slowly and becoming hypothermic themselves. The pair eventually withdrew from the 100-mile event at the 130-kilometre mark over their concerns for the safety of other runners still on the mountain.

Southern Patagonia is an unforgiving place. “Magic” is a word that is often used here: it is magic to have had the opportunity to pass through a place that is so thoroughly wild and untouched. But that wildness comes with challenges in communication and access. There is no cell service, and radio communication is often impeded by the terrain. Access is only on foot or by helicopter, weather permitting–and the weather does not permit much.

The racer who the Argentinians assisted to camp, along with one other, ended up spending three nights on the mountain in a rudimentary camp awaiting air rescue. They finally walked out, accompanied by a Chilean search and rescue team. A helicopter was not able to retrieve Martínez Rueda’s body until Tuesday; it was located under a metre of snow.

The racer who the Argentinians assisted to camp, along with one other, ended up spending three nights on the mountain in a rudimentary camp awaiting air rescue. They finally walked out, accompanied by a Chilean search and rescue team. A helicopter was not able to retrieve Martínez Rueda’s body until Tuesday; it was located under a metre of snow.

There are many questions being asked, and many criticisms of how the race has handled both safety on course and communications during and after this accident. The police chief claims that there was a feasibility report prepared prior to the race, recommending that the event not go ahead. Race director Stjepan Pavicic counters that argument, saying the report referred only to legal issues about road access and not about safety concerns.

Several racers have voiced their support of the race and its organization. Notably, Genís Zapater of Spain, who took third in the Ultrafiord 100K last year, and who won the 70K this year, says that “running in these latitudes is not for everyone,” and that some racers show up without sufficient experience or not carrying appropriate gear. (Genís hit the finish line in under 7 hours this year, just as the bad weather was setting in. Over a hundred of racers were still up top at that time, some taking over 17 hours to complete that same route).

There will no doubt be much said and written about this tragedy over the coming months: what the race organization could have or should have done, and how much responsibility lies with the racers themselves. Last year, I know that numerous racers did not carry their “obligatory” gear. Not only is this is a type of cheating, which in many races would result in disqualification, but in a race that pushes the extremes like Ultrafiord, that gear–spare clothing, headlamp, extra batteries–may also save your life.

Pavicic told the Chilean press that he believes part of the responsibility for the death lies with the racer himself (we do not know at the moment why he was dressed only in shorts, and whether or not he was carrying the required gear). However, Pavicic acknowledges that his organization could do better by being more strict about who may enter Ultrafiord, verifying that runners are carrying the required gear, and improving communications along the course.