Carbon fibre plate tech: the Calgary connection

The technology behind the carbon fibre plate in running shoes was born at the University of Calgary's kinesiology faculty

Contrary to popular belief, the technology behind the carbon fibre plate did not start with Nike. More than 20 years ago, Darren Stefanyshyn was studying ways to improve athletic footwear for his Ph.D. thesis under Dr. Benno Nigg at the University of Calgary’s Faculty of Kinesiology. Years later, Stefanyshyn, in turn, supervised Geng Luo, who went to work for Nike upon obtaining his own Ph.D., and who was directly involved in the development of the Vaporfly 4%.

RELATED: Nike’s Vaporfly 4% data sheds light on how the shoe works

Stefanyshyn spoke to us last week from his office in Calgary.

Origins of the research

“At the time, we were looking at different activities, including running and jumping, and collecting baseline data on the movements that are limiting factors… what we found was that the shoe acts as a brake–an absorber of energy–and we were studying ways to modify that. The simplest one was to stiffen up the shoe by putting in a carbon fibre plate.”

RELATED: New Balance releases carbon-plated shoe

Stefanyshyn explains that carbon fibre was not common at the time, and it was not easy to get. Shoe companies wanted the research, and researchers needed the resources a corporation could provide. In collaboration with Adidas, Stefanyshyn and his colleagues experimented with putting a carbon fibre plate into a running shoe, and tested the theory that it would enable runners to sprint faster and run more economically.

How would the carbon fibre plate work?

Creating a shoe that maximized performance meant understanding how energy was generated and lost in the joints of the foot and leg. “Nobody had looked at the foot,” says Stefanyshyn. “The ankle is like a spring—it absorbs, and then generates, energy. The knee too. But in traditional shoes, the foot wasn’t doing that–it was only absorbing energy. There was a disproportionate unbalance that didn’t make sense from a performance perspective. We tried a few things, and the easiest thing was to try to eliminate energy lost in the foot. It came down to not letting the foot bend so much, which meant adding stiff plates.”

The goal was to try to make the shoe behave more like a spring. Stefanyshyn and his colleagues were not entirely successful at this, but they did find that the addition of the carbon fibre plate removed some of the energy loss, so the athlete had more energy to execute the movement.

RELATED: Project Carbon X: Breaking2, Hoka-style

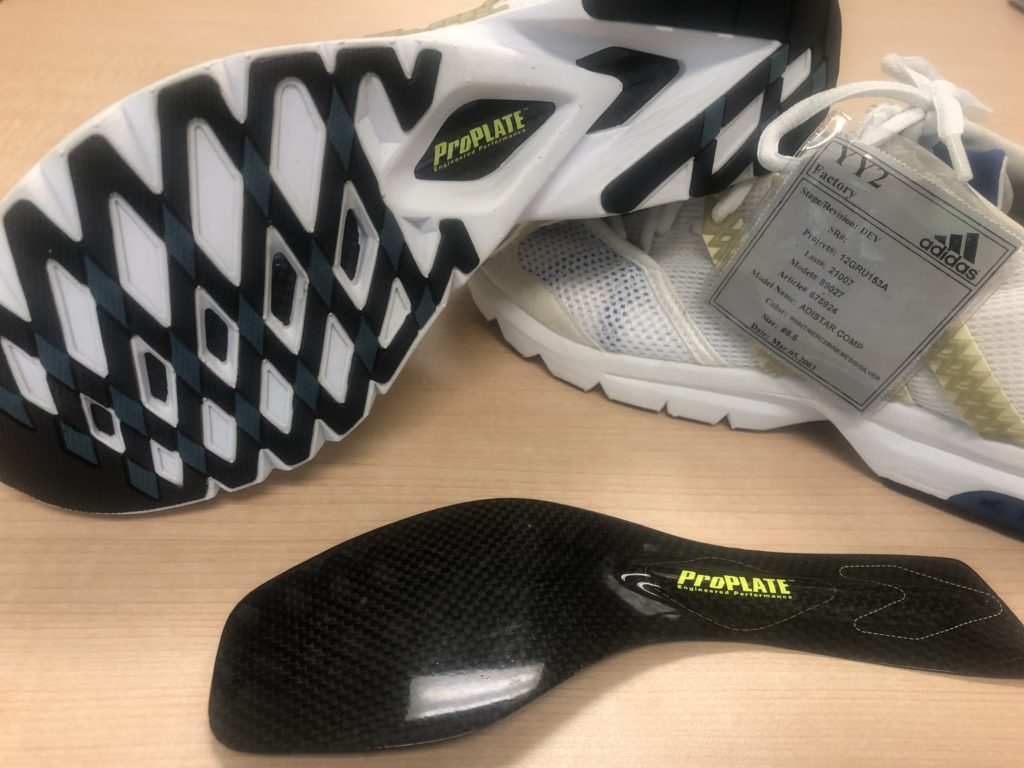

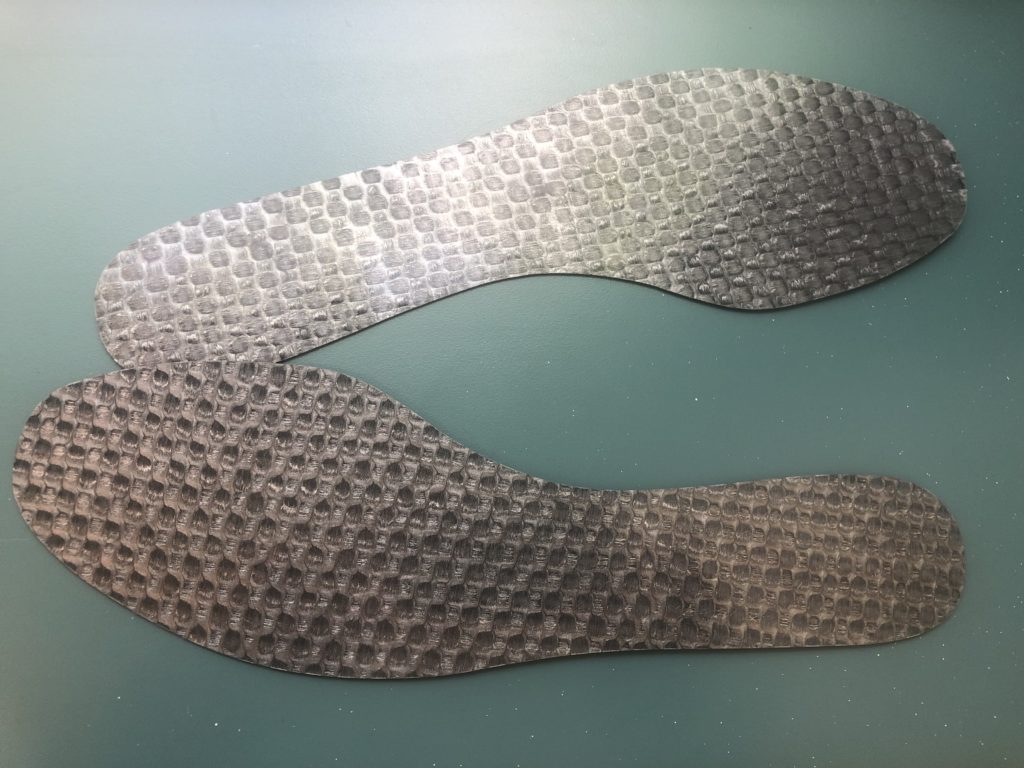

The original carbon fibre plate shoe

The first iteration of the carbon-fibre plate was the ProPlate, which appeared in an early version of the Adidas AdiStar in the early 2000s. Researchers in the faculty have since worked with companies like ASICS, New Balance and Brooks, as well as Adidas and Nike, all of whom have experimented with incorporating a carbon fibre plate into their products.

Recent studies have found that while the introduction of a curved carbon fibre plate minimizes energy loss, it doesn’t behave like a spring, exactly. And those commenting on the Nike Vaporfly 4% and NEXT% in particular speculate that the spring-like bounce produced by the shoe comes more from Nike’s ZoomX foam than from the plate. Here’s what Stefanyshyn has to say about that: “From all of our research on plates as well as foams and cushioning materials, I speculate that both play a substantial role in the improvement.”