How to run your best half-marathon

For tens of thousands of Canadians, the half-marathon is the ultimate running event. It requires that we work for our achievement, but it doesn’t leave us destroyed for weeks after crossing the finish line.

But 21.1K is still a big task to wrap your head around. We tasked three of Canada’s best running and conditioning coaches to develop a plan so that you can run your best half ever.

The Three Phases of half-marathon training

Montreal Olympic Club coach John Lofranco breaks down how to prepare for your best half-marathon

The Base Phase

The base phase is probably the most important phase, though many runners tend to skip it and go right for the specific work. This phase can last as long as you need it to, but you probably should have at least six weeks, and ideally 12 weeks of base work in a cycle of two weeks building up and one down week for recovery. It could even be longer.

The goal here is to gradually grow the amount of running you do each day and each week. Make that your priority. You will do some workouts, yes, but the important thing is getting your body used to a lot of running. How much? It depends on how much you are doing now. If you are starting at 40k per week, and you have six weeks of base, you might be able to get up to 60k. If you have 12 weeks to work with, going from 40k per week to 80k–90k per week is not unreason- able. Increasing your volume by 10k per week is 2k per run if you run five times a week (and, ideally, you should be running that much). That’s 10–15 minutes of running for most, which is doable.

Workouts during this phase should be nothing more than short strides or hill sprints (to get your leg turnover going) and some light tempo or fartlek runs. The main workout of the week is the long run. If your goal is to finish a half-marathon for the first time, start at whatever your longest run distance is, be it 12k or 16k, and add 2k per week here as well.

Specific Phase

Once you have built up a good base of mileage, and you’ve grown your long run to around 18–25k (depending on your goal), you’re ready to get specific. This phase can last 8–12 weeks, depending on your schedule.

Whatever you’ve built your mileage up to, keep it there, on a cycle of two weeks at near your top mileage and one week back down at 60–70 per cent of that.

The tempo run is going to be the main workout of this phase. The best way to prog- ress this workout is to see how long you can go. So if you start with a 20-minute tempo at your goal race pace, grow that by five minutes each week until you get to 40 minutes. You’ll do some intervals as well, but make sure to prioritize the tempo run, along with the long run.

Taper Phase

This phase will last two weeks at most. The goal here is to unload all the training you’ve loaded on in the previous weeks and months. Reduce the total volume that you run, down to about 60 per cent of your maximum. Don’t be afraid to cut back on your volume.

While you reduce volume, you want to keep intensity about the same, and keep it specific. In the last two weeks, go for a 20-minute tempo run at your race goal pace. The goal is simply to remind your body of the pace you want to run. You should also keep up the strides, and do a workout that is faster than race pace, but not too long or hard. So perhaps 8×400 m at (current) 5k race pace, with 2–3 minutes of recovery. That should be pretty easy. The volume is low and there is a lot of rest. The goal there is to get your legs turning over so you don’t feel heavy on race day.

Ideally you focus on good sleep and nutrition habits all of the time, but in this final phase, they are even more important. Rest up and prepare for your race.

Five ways to improve your half-marathon time

By Jon-Erik Kawamoto

Fuel efficiency is a sought after perk when purchasing a vehicle. Using less fuel means you can get farther and spend less. Running a half-marathon is no different. A more economical runner will be able to keep that smooth stride in the last few kilometres of a 21.1k race. Improving your running economy should be one of your main goals if you want to run a great half-marathon.

Contributors to running performance

Running performance is a complex outcome to predict, but there are three big factors:

VO2-MAx: a well developed maximum oxygen uptake and delivery system.

Lactate threshold: the ability to main- tain a high level of aerobic intensity, just below your VO2-max, usually what you can run all-out for 60 minutes.

Running economy: good overall fuel efficiency

Some scientists argue that VO2-max does not increase all that much during a runner’s career however, the ability to maintain a high lactate threshold and running economy seem to be the most malleable. Running economy is simply a term used to describe your energy demand for a given velocity of sub-maximal running. If you lower your energy demand for the same velocity of running, it means you have improved your running economy.

How to improve running economy

There are five ways to improve your running economy: building endurance, resistance training, plyometric training, flexibility training and nutritional supplementation.

1) Building Endurance

To be a better runner, the most important thing you need to do is, of course, run regularly. Successful distance runners typically train for many years, logging thousands of K’s of varying intensities. Over time, lots of running improves skeletal strength, muscle oxidation capacity, particularly by increasing capillary density and improving mitochondrial function and volume. Mitochondria are the powerhouses of your cells, as they are responsible for producing the majority of the energy-rich adenosine triphosphate (ATP) molecules. Your body’s ability to clear metabolic by-products improves, as does the volume of your red blood cells. These adaptations will improve oxygen delivery and utilization and thus, your running economy.

THE TAKEAWAY: If your body can handle the miles, consider increasing your running volume, but by no more than 10 per cent per week.

2) Resistance Training

Effective strength training routines should incor- porate multi-joint free weight exercises that relate to running. Such exercises include squats, dead- lifts, lunges, jumps and sprints. Incorporating this type of training into an existing running program improves running economy thanks to neuromus- cular adaptations, which basically is your brain’s ability to communicate, recruit and use your muscles when you run. Your muscles will also work at a lower percentage of a newly heightened strength capacity, meaning you’ll use less energy and oxygen to run at lactate threshold pace.

Also referred to as maximal strength training, the idea with this type of training is to use weights heavy enough to promote strength gains and target fast twitch muscle fibres, which you’ll recruit when you get fatigued during a long distance run. Use manageably heavy weights for five reps or less.

THE TAKEAWAY: Lift weights 1–2 times a week in the strength training zone of 5 or less repetitions per set when performing squats, deadlifts or lunges.

3) Plyometric Training

Also referred to as jump training, plyometric training will increase the stiffness of the musculotendinous unit, which allows the body to store and utilize elastic energy more efficiently. With each running stride, your muscles and tendons store and then output energy. If your muscles and tendons do not have a certain level of stiffness, the energy will be lost as heat, however, if you improve their stiffness, you can use this energy in your next stride. This will shorten your ground contact time and improve your running efficiency.

THE TAKEAWAY: Add in 1–2 jump training sessions in per week. Aim for 50–70 total repetitions per workout.

Joint flexibility is influenced by the soft tissues surrounding the joint, particularly muscles and tendons. If these tissues are too tight, joint biomechanics may be compromised, which causes overuse injuries. If the tissues are too loose, elastic energy will not be stored or used, reducing running economy. Being on the tighter end of the spectrum, but with good joint mechanics, may be beneficial, as being less flexible allows for greater storage and usage of elastic energy and a lower oxygen requirement. However, it must be said that stretching shouldn’t be discounted, as some runners need to improve their flexibility in order to improve joint function and running mechanics.

THE TAKEAWAY: Stretch if you’re too tight, but don’t over- stretch. Stay on the tighter end of the spectrum but ensure you have good joint mechanics.

Popeye might have been onto something. Green leafy vegetables such as lettuce, spinach, arugula, celery and beetroot are rich in nitrates, an important compound that can improve circulating nitrite concentrations. Nitrite converts to nitric oxide, an important signalling molecule that can modulate ske- letal muscle function. Increasing nitric oxide concentrations can lower the oxygen demand of running at lactate threshold pace.

THE TAKEAWAY: It might be a good idea to have a daily salad or glass of beetroot juice.

What is the fartlek?

By Nicole Stevenson

Over the years, each coach I’ve worked with has included fartlek runs in the off- season for fun and as I built for a goal race, such as a fast half-marathon. This funny sounding Swedish word means “speed play,” and is an informal way to develop speed, strength and endurance as you build for your goal half-marathon.

During the first few weeks of your half- marathon build, throw in a fartlek run in the middle of an easy run. Here’s how:

Start with a 15–20 minute warm-up of easy running, then let the fun begin. Once you’re ready, do random pick-ups (timed or just by feel) each between 30 seconds and three minutes long, followed by one minute of easy recovery running. During these fartlek pick-ups, focus on form instead of effort or pace. While you fartlek, focus on different aspects of your running form:

INCREASE your running cadence by taking shorter, quicker steps, even exaggerating slightly. You’ll naturally change to a mid- foot strike.

BREATHE steadily down to your belly, then pushing out thorough exhalations. Try one of these breaths at least once during each interval.

DRIVE your elbows back, propelling your arms to drive your knees higher on the upswing.

DROP your shoulders down, letting your arms act as levers without movement in your shoulders.

SMILE! Relax your face and have fun.

Training right in the last ten weeks

By John Lofranco

The Specific Phase

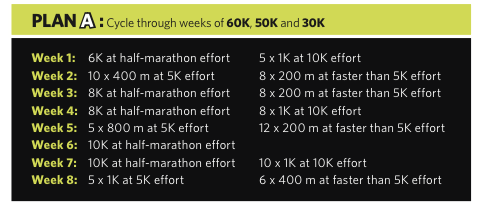

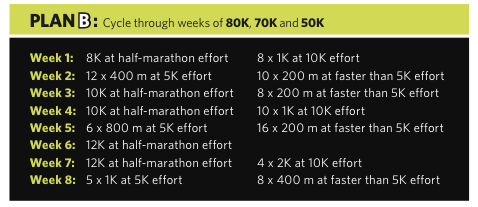

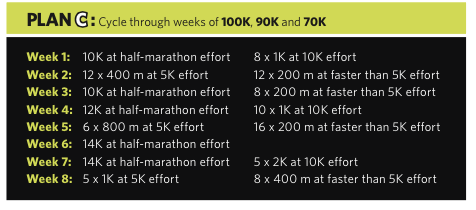

This phase is to be started about 10 weeks out from your goal half-marathon. Leading up to the specific phase, build a base by running consistently and doing strides at the end of easy runs and a weekly fartlek workout. Enter the specific phase only after you’re able to handle one of these three plans. Below are two weekly sample workouts (only do one workout on lowest volume weeks). Separate these two workouts by at least two days so that you can recover, and include the mileage in your overall weekly target.

The Taper Phase

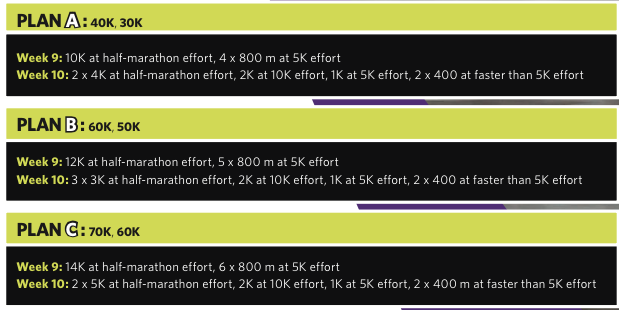

Two weeks, two workouts per week, continue with strides.

A Boom and a half

By Roger Robinson

The growth event of our time, the race that best embodies the exponential energy of the running boom, is the half-marathon. Every year, new ones spring up all over Canada. The demographics show why, since the half is the distance where a new wave of runners, mostly female, clearly predominate.

A perfect fit for the busy modern runner, the half is long enough to make completing the course a satisfying challenge, yet doesn’t require such long hours as the full marathon, in training or on race day.

A perfect fit for the busy modern runner, the half is long enough to make completing the course a satisfying challenge, yet doesn’t require such long hours as the full marathon, in training or on race day.

It’s also a race of the modern era. Today’s runners define themselves by best times over standard distances. But that’s a relatively new trend.

In the early days, road races usually followed geography. North America’s oldest, Hamilton’s Around the Bay, founded in 1894, was and is 30k because, well, that’s how far it is around the bay. The U.K.’s first half-marathon, created in 1904, went from Morpeth to Newcastle, 21.91k for several years, but varying later with road construction. It didn’t occur to anyone to make it a half-marathon for the simple reason that there was no standard marathon distance. It wasn’t until the late 1940s that every race calling itself a marathon was 42.195k .

Some early races, cashing in on the huge fame of the 1908 Olympic marathon, were dubbed “modified marathons.” One that went from the Bronx to New York’s City Hall in 1911, just over 12 miles, ended in scandal and media sensation. Runners were permitted to “remove their street clothes” in the committee room, but numbers far exceeded expectation, so more than 500 sweaty and sparsely-dressed men were noisily scrambling around City Hall for space to change and “rub down.” A meeting of shocked female teachers was escorted to safety by the police.

Given all these variables, what was the first half-marathon? Historian Andy Millroy found a “semi-marathon” in London in 1919. The first to be actually called a half-marathon was in Bogota, Colombia,in1938.TheVictorianMarathon Club held a half-marathon in Moonee Valley, Melbourne, in 1953.

The modern boom in the half began with the Route du Vin in Luxembourg, founded in 1961. Then Freckleton, a little place in Lancashire, England, held one in 1964, and a young student runner called Ron Hill showed up and ran an extraordinary 1:04:00, the first sign of his stellar marathon career that lay ahead.

“The half-marathon is great, as you can push yourself almost flat out without the risk of blowing up,” Hill told me after he ran his last half-marathon at age 70 on the same course in 2009.

The oldest half in Canada with a conti- nuous history is probably Vancouver’s Delta Half-Marathon, which celebrated its 25th year last August. In 1979 it was the only half- marathon in the nation. Today you could run one every week and never get to them all.

The “New” Intervals

Teach your body to recover on the fly with this variation on the tempo workout

By John Lofranco

The Monafartlek

There are many ways to build a workout in this way. One well-known version is called the “Monafartlek,” after Steve Monaghetti, an Australian distance runner and Olympian. He modified the classic fartlek workout by making the recovery more challenging.

It goes like this: 2×90 seconds, 4×60 seconds, 4×30 seconds, 4×15 seconds at 5k effort. The recovery is equal (so 90, 60, 30 or 15 seconds as applicable) but at a “float” pace, meaning faster than jogging (close to marathon pace).

The great thing about this workout is how adaptable it is: the hard sets can get harder as you go, the floats can get faster, too, or if you are not having a great day, you can temper the pace, but it’s still at least a solid 20-minute effort.

Floating and 400s

Another option is to run it on the track at 8×400 m at your 5k pace, with 200m “float” recovery. I like to end this one (after the eighth float) with a fast 200m to give a round 5k of running. I’ve coached runners that have run within a minute of their 5k PB in this workout. That’s a real confidence boost. Unlike the Monafartlek, however, this one encourages strict adherence to pace and distance on the track.

For half-marathon training, you can run between 30-40 minutes, alter- nating between 10k and marathon pace. World renowned coach Renato Canova alternates 400m at 10k pace and 1,000m at marathon pace to start, and over the course of a season, gradu- ally changes the balance so it ends as 1k at 10k pace with 400m recovery at marathon pace.

A gentler version of that is to go with one minute at 10k and four minutes at marathon pace and work back to three minutes and one minute, respectively.

What’s great about these “new” intervals are that they teach your body to recover while still running fast. There are two applications for this. The first is obvious: this will help you weather hills, surges and other pace changes in a race situation. The second is something called “the lactate shuttle.” Not to get too technical, but essentially, this workout trains your body’s ability to use for energy some of the lactate produced when you run fast.

These are not replacements for classic interval workouts, but if you are sick of 10×400 m or 5x1k or 3–4×1 mile week-in, week-out, these can be a nice addition to your half-marathon training plan.