Inside the world of elite training

From biosensor tech to anti-gravity treadmills, elite runners are increasingly incorporating technology into their training

By: Andrea Hill

Sprinter Aaron Brown is a visual learner.

His coaches can tell him to adjust the angle of his body as he explodes off the starting blocks. However, unless he can see it, it’s hard for him to understand and make the change.

So when Brown started training as a college athlete at the University of Southern California in 2010, he was glad that track coaches there were using Dartfish, a sports visualization software. Coaches would film Brown, then watch the footage with him in slow motion. They broke down and measured Brown’s movements in front of him on a screen, providing the visual feedback he needed to become a more efficient runner.

“I’d hear an instruction and I wouldn’t be able to associate what they were telling me with what I was doing,” Brown recalls.

“[Dartfish] helped me improve my connection between what my coach was teaching me to do and the movements that I was making.”

Dartfish was one of Brown’s first brushes with technology in the world of running, but it wasn’t his last. While in college, he realized all his teammates and competitors were employing some form of technology in their training, from using apps to track workouts to utilizing tools to speed up recovery.

“It’s kind of like if you weren’t using it, then you were almost antiquated and training like an old caveman,” Brown says. “You have to keep up with the times, and you don’t want anybody else to have an edge on you. Everybody’s adopting and seeing the advantages of using technology. So everybody has had to follow suit.”

Shoe companies are trying to “get an edge” by re-engineering shoe design

Technology is also affecting what athletes wear, with shoe and apparel companies producing footwear and clothing engineered to be fast and aerodynamic.

Nike, for example, made headlines when it unveiled its Vaporfly Elite shoes during its ambitious attempt to break the two-hour barrier in the marathon in 2017. The shoes, which feature a curved carbon-fibre plate within the sole of the shoe, were touted to make runners four per cent more efficient–and subsequent research has supported this claim. Marathoner Eliud Kipchoge ended up running a 2:00:25 in Nike’s Breaking2 project and is expected to make a second attempt to break the two-hour barrier later this year.

“A lot of times you think of technology as more kind of computer based, but technology is everything they’re wearing: the shorts, their shoes, all of that,” says Eric Golberg, the lead coach of sport conditioning with the University of Alberta’s Sport Performance Centre in Edmonton.

“The shoes and looking at our runners’ efficiency and how a shoe can affect that, that’s a really big piece. As technology progresses with the shoes and running, I think that you can’t understate the kind of effect that will have.”

Aaron Brown says that, as a sponsored Nike athlete, he is constantly trying out new footwear the company is producing.

“[Nike] is always trying to improve, get an edge where they can, because every 10th of a second counts, every hundredth of a second counts. The little details matter,” he says.

GPS watches aren’t just for rec runners

Golberg said that in recent years, he’s seen a rise in technology used for running, particularly when it comes to monitoring technologies such as global positioning system (GPS) watches and affiliated apps.

“This is a boom for the general runner. We’re in it right now or have been in the last five to 10 years,” Golberg says.

Gabriela DeBues-Stafford, an elite middle-distance runner who this summer became the first Canadian woman to run under four minutes for the 1,500m, self identifies as a “low-tech” runner. However, she still uses a GPS watch for training to track her longer runs and to time herself on the track. Her current model is the Garmin Forerunner 235, which she pairs with a chest-strap heart-rate monitor and syncs with the Garmin Connect app.

DeBues-Stafford’s father, James Stafford, represented Canada at four World Cross Country Championships in the 1980s. DeBues-Stafford says it’s remarkable to talk with him about the methods he used to determine how far he ran in the era before GPS watches. Stafford would use a piece of string to plot out a route on a map, then measure the string and make a distance calculation based on the scale of the map.

“It’s pretty cool that we have a GPS on our wrists now that can tell us instantaneously how far we’re running, what pace we’re doing,” DeBues-Stafford says. “It’s such a convenient thing that has been introduced in running.”

Basic GPS watches tell athletes their distance, pace and time, while more advanced watches use infrared light to read heart rate, which allows the devices to estimate a runner’s maximal oxygen uptake (VO2 max) and give feedback about the optimal amount of recovery needed after a workout.

DeBues-Stafford says that, as an elite runner with a coach and support team, she mostly worries about tracking distance and time and lets her team make decisions about when she needs to recover and when she needs to push hard – even if her watch advises against it.

“Sometimes you need to train when you’re not fully recovered. And that’s kind of the point,” she says.

Trent Stellingwerff, the sports science, sports medicine and innovation lead with Athletics Canada, says GPS watches that automatically sync with apps such as Garmin Connect or TrainingPeaks allow coaches to become better informed about their athletes’ training. That’s particularly important for distance athletes, many of whom log long, easy kilometres without a coach present. Stellingwerff estimates most distance running coaches directly observe less than 20 per cent of their athletes’ runs.

“The coach isn’t there, and there can be massive disconnect between what the coach thinks the athlete’s doing versus what the athlete’s actually doing,” he says. “That’s where technology can sometimes step in.”

With technology, coaches can log into an app or website and see how many kilometres their athletes logged, at what speed and at what effort.

“The coach at their house can look on a website and say, ‘Oh, cool, for 80 per cent of that training I can’t see, I now at least have something that indicates that the athlete is on track and doing what I hope they’re doing,’” Stellingwerff says.

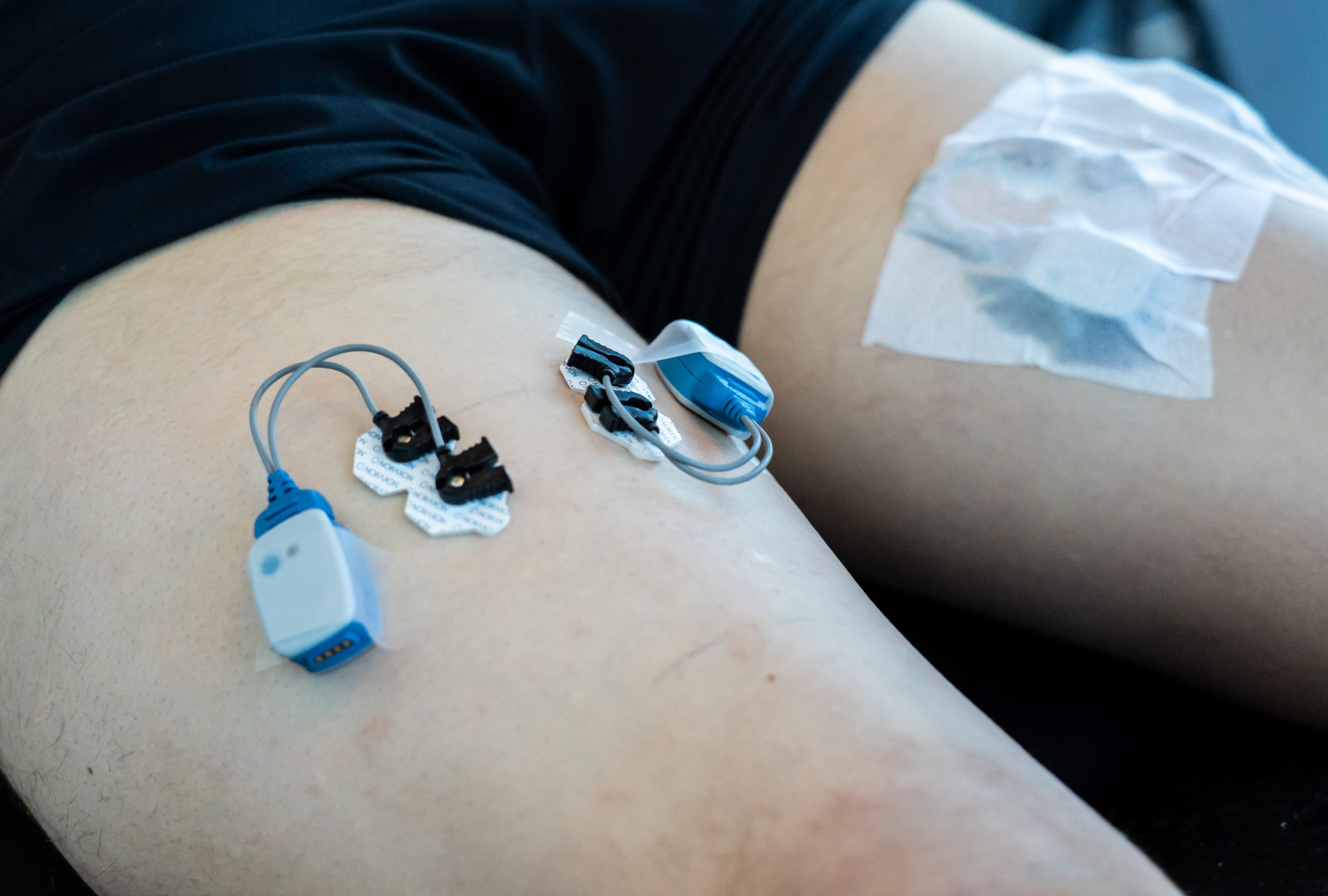

Biosensor technology is providing real-time feedback to coaches and athletes

Watches aren’t the only tools allowing athletes and coaches to monitor training.

Heather Sprenger, the research and innovation lead with the Canadian Sport Institute Ontario, says the telemetry pill, that transmits data on gastrointestinal core temperature, is one of the most interesting pieces of biosensor technology she has seen athletes use. These are particularly useful for tracking heat stress in athletes competing in longer running events, such as the marathon, and the technology is typically only available to athletes who work with a sports scientist or integrated support team.

Runners swallow a pill before doing a hard workout or race simulation, allowing coaches to read information about their temperature in real time.

“It gives us an indication of whether they’re overheating or getting to that critical temperature where they could start seeing some compromised performance in physical work capacity as a result of being too hot,” Sprenger says.

Knowing how an athlete responds to heat allows coaches and support staff to develop appropriate cooling strategies before, during and after a race to ensure athletes don’t run into trouble.

Athletes are increasingly turning to technology for speed recovery

In addition to seeing a growth in the use of GPS watches, Sprenger says she is also witnessing more instances of runners accessing technology to help them recover. For example, an increasing number of sports facilities are providing access to AlterG Anti-Gravity Treadmills so athletes can recover sooner after an injury.

“The transition back from an injury has been advanced and accelerated due to technology,” Sprenger says. She predicts that, as demand for these types of devices increases, more clinics will make them available and they will become more mainstream.

HydroWorx underwater treadmills, which first appeared on the market in 1998, allow athletes to run in warm water of varying depths. The heat decreases inflammation while the water’s buoyancy means runners aren’t pounding the ground with their full weight.

The AlterG medical device company, founded in 2005, sells treadmills that allow athletes to run at a lesser proportion of their body weight by employing differential air pressure technology first developed for NASA. NASA needed a pressurized air chamber that simulated the gravity of Earth so astronauts could exercise while in space. AlterG reverse engineered that to create the AlterG Anti-Gravity Treadmill. While using the treadmill, runners’ lower bodies are locked in a pressurized air chamber that increases buoyancy, simulating a lower-gravity environment, allowing them to put less stress on their bodies.

Kate Van Buskirk, an elite middle-distance runner and host and producer of Canadian Running’s The Shakeout Podcast, says most elite Canadian distance runners use an AlterG treadmill at some point, either as a rehab tool or as a form of cross training.

Van Buskirk ran on an AlterG treadmill after she tore a hamstring tendon in 2014 and more recently this spring following knee surgery to repair a torn meniscus. She also regularly uses the machine as an injury prevention tool for some of her easy runs on it.

“It’s just eliminating a little bit of the impact on my weekly volume,” she says.

Van Buskirk also uses a compression boot as a recovery tool. The device zips up the leg from toe to hip like a giant compartmentalized blood pressure cuff and a generator feeds in air, applying pressure to the various compartments.

“It feels a little weird at the time, but it’s meant to help stimulate the recovery of your legs after a hard session,” Van Buskirk says.

Altitude tents are giving athletes the benefit of living at altitude from the comfort of their homes

Aside from injury prevention and recovery, runners are using technology to improve their performance.

One of the tools in Van Buskirk’s toolkit is an altitude tent. She props the structure over her bed at home and a generator pumps deoxygenated air inside, simulating the effects of being at altitude, which encourages her body to produce more oxygen-carrying red blood cells. During the first phase of her training cycle, Van Buskirk estimates she spends between 12 and 15 hours a day in her tent.

Many elite marathoners spend long stints living and training at high-altitude locations such as Kenya or Colorado – Van Buskirk has spent several weeks training in Flagstaff, Ariz. – but that’s not a realistic option for everyone, van Buskirk included.

“(My altitude tent) is sort of the way that I balance both my living in Toronto, but also getting that altitude exposure,” she says.

Technology is still no replacement for hard training.

Brown says he sees his competitors on the track trying out new shoes as well, but he doesn’t let that psych him out. While he appreciates the benefits technology brings him and other athletes, he knows it’s only part of the puzzle.

“And at the end of the day, it’s still going to come down to what’s tried and true: working hard at practice, having natural talent and executing on the day. Those are the main things that are going to lead to you being faster,” he says.

That sentiment is echoed around the running world, says Van Buskirk.

She likes to remind people that some of the best runners come from East Africa, where few athletes have access to technology; some athletes don’t even have shoes.

Van Buskirk says while some people might like to believe technology can serve as a shortcut to getting faster or healing more quickly, at the end of the day there’s no substitute for being a smart runner.

“The biggest piece of advice I would have would be to not live and die by the technology and also not to let it take over so much that you’re getting away from your ability to engage your own body,” she says. “Technology can be a great supplement, but I would never pin my success or my failure on a use or lack of use of technology.”

This story originally appeared in the November & December 2019 issue of Canadian Running.

Andrea Hill is a marathon runner and the city editor of the Saskatoon StarPhoenix newspaper in Saskatchewan