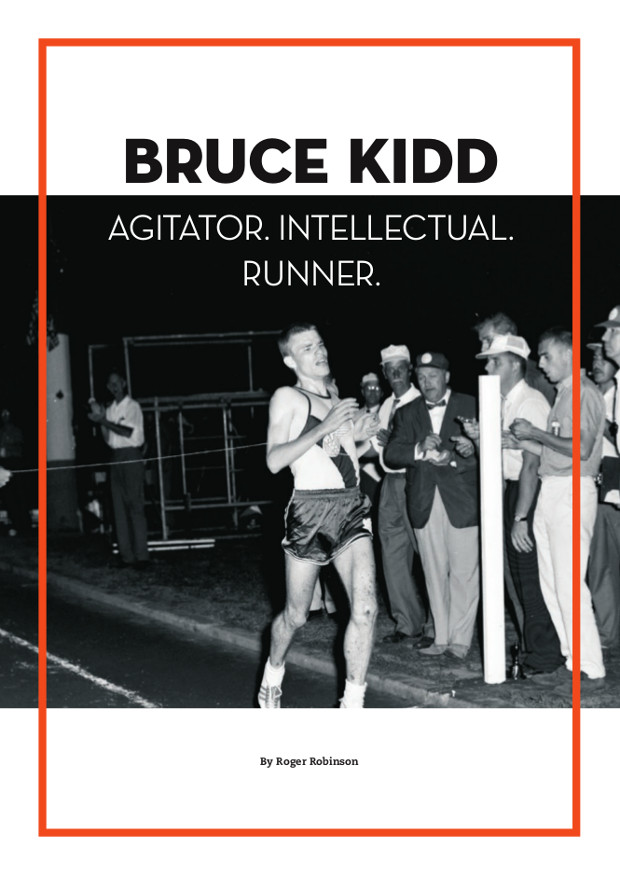

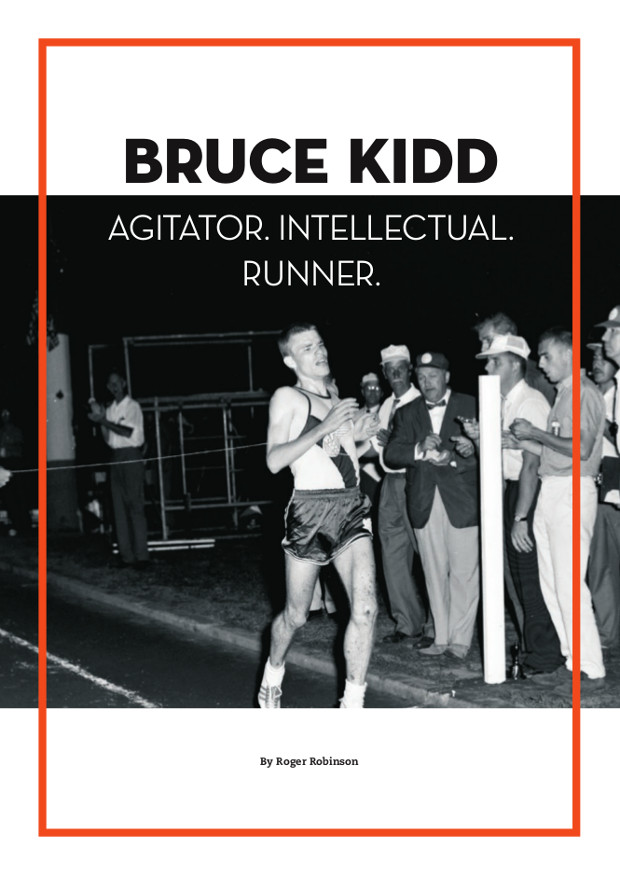

Bruce Kidd: Agitator. Intellectual. Runner

Canada’s great runner of the 1960s is a man of ideas and ideals

“In the bunch is that fabulous Bruce Kidd, the 19-year-old Canadian whom some experts believe to be the greatest long- distance runner ever seen!”

“In the bunch is that fabulous Bruce Kidd, the 19-year-old Canadian whom some experts believe to be the greatest long- distance runner ever seen!”

–Voice-over, Pathé News, November 1962.

It’s the British Empire Games six-mile race, 1962, a blazing 37 C summer day in Perth, Australia.

“Imagine running six miles in this boiler-house heat!” gasps the commentator. Canada’s Bruce Kidd, wearing a big white cap against the sun, lives up to his reputation for greatness. He accelerates away from a world-class field, wins by eight seconds and at the finish whirls and tosses his white cap high in the air with exuberant teenage delight.

Fifty-two years later, Bruce Kidd still stands – for his short period at the top – as Canada’s greatest ever long-distance track runner. He also stands – for a much longer period – as an important sports intellectual, thinker, scholar, writer, opinion leader, agitator and activist. For five decades he has led, inspired, provoked and annoyed people – annoyed them more because in the fullness of time he has usually been proven right.

Every conversation with him confirms that Kidd is one of the most thoughtful and interesting people in the world of running. His wider resumé earned him appointment in 2004 to the Order of Canada. Quite an achievement for someone who was once savaged by Canadian sportswriters as “immature,” and “ungrateful,” and who provoked graffiti on university walls like “Bruce Kidd is a Commie fag.”

Kidd is the only Canadian track distance runner ever to make top three in the Track & Field News annual rankings (5,000m, second, 1962), and the only one to win a gold medal (plus a bronze) in the Commonwealth Games 5,000m or 10,000m (then known as the Empire Games and three-mile and six-mile races). Canada’s other medallists at those distances are Scotty Rankine (two silver, one bronze, 1934, 1938), Paul Williams (10,000m bronze, 1990) and Cam Levins (bronze in the 10,000m in 2014). Kidd is also the world’s only runner to have a documentary film made about him with a ponderously pretentious voice-over written by a great British poet having a bad day – the National Film Board of Canada’s 1962 production called Runner, with commentary by W. H. Auden.

Kidd is the only Canadian track distance runner ever to make top three in the Track & Field News annual rankings (5,000m, second, 1962), and the only one to win a gold medal (plus a bronze) in the Commonwealth Games 5,000m or 10,000m (then known as the Empire Games and three-mile and six-mile races). Canada’s other medallists at those distances are Scotty Rankine (two silver, one bronze, 1934, 1938), Paul Williams (10,000m bronze, 1990) and Cam Levins (bronze in the 10,000m in 2014). Kidd is also the world’s only runner to have a documentary film made about him with a ponderously pretentious voice-over written by a great British poet having a bad day – the National Film Board of Canada’s 1962 production called Runner, with commentary by W. H. Auden.

Kidd’s interest in athletics began with a lucky break for his father, J. Roby Kidd, a leading adult educator. Due to attend a conference in Denmark in 1952, he was asked by the cbc to divert to the Helsinki Olympics as a one-man crew to shoot film for their primitive new television operation. When he brought the footage home to edit, a nine-year-old Bruce sat alongside.

“The level of achievement with athletes like the great runner Emil Zatopek and the Jamaicans showed me a whole world of excellence. And from my father’s stories I learned about peaceful inter-cultural exchange, the way Games competition helps to produce communality – even the Russians were partying, the athletes didn’t go away and hate each other,” he said in a conversation this year.

The second formative moment came when the family attended the British Empire and Commonwealth Games in Vancouver, August 1954. “I watched the Bannister-Landy mile live, the first complete distance race I’d ever seen. My father’s Helsinki footage was only clips. I was thrilled by the way John Landy took off like a deer and raced hard the whole way. Helsinki and Vancouver were when my sporting ambitions turned from baseball and hockey to the Olympics.”

Those ambitions co-existed with precocious running talent. The first opportunity to race longer than 220 yards came in 1957, in Toronto’s Malvern Collegiate junior harrier championship. With images of Zatopek and Landy racing through his 14-year-old head, Kidd took off fast, and hung on to win. He was less successful in the Toronto championships, but failure spurred him to begin semi-systematic training. He spent the next winter running around cricket fields in Jamaica, where his father was setting up a university extension department. This was a boy with plenty of inner motivation. He returned to Toronto and won the city championships for the 880 and the mile.

At just 15, he began training with Fred Foot, the 1956 Canadian Olympic coach, who

mentored the East York Track Club and University of Toronto teams. “Fred changed my life. He was an exceptional planner, analyst, and motivator,” Kidd said. Learning from the Europeans, Foot constructed a program of interval training and fartlek runs, and taught Kidd how to race. The teenager was training daily with older mature runners, some with international experience, and they aimed high. “We subscribed to the overseas magazines, we argued about the most important races in the world as if we should be there, trying to win. And they were ambitious in their careers and university studies, too. It was a heady atmosphere,” Kidd remembers.

Home life was equally stimulating. Kidd’s parents were social democrats and activists for independent Canadian nationalism, improved access to education and other causes. Every family meal brought discussion of ideas, ideals, and issues. Kidd became knowledgeable about history and politics at the dinner table. The whole family worked on election campaigns for the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, the predecessor of today’s New Democratic Party.

“I was so totally engrossed in the 1958 federal election that I predicted to my amazed history class that the ccf would form the next government. When the Progressive Conservatives won a landslide majority I was heartbroken,” Kidd wrote in a recent book.

As a runner, he tasted only victory. He set 15 Canadian records and won 18 senior championships. In 1961, he won two American senior indoor titles. There was controversy about whether a 17-year-old should be allowed to compete. He graduated from high school with first class honours in every subject. Offered scholarships all over the U.S., including Harvard, he chose the University of Toronto, a decision that still shapes his life.

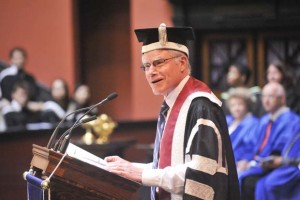

“U of T gave me an extraordinary education. I was able to study with the giants of Canadian political economy and government at a time when faculty-student interaction was common and often social,” Kidd wrote. A full professor and former dean, he is currently interim principal of the University of Toronto Scarborough – executive head of an entire major campus. He has become one of the academic giants he once admired.

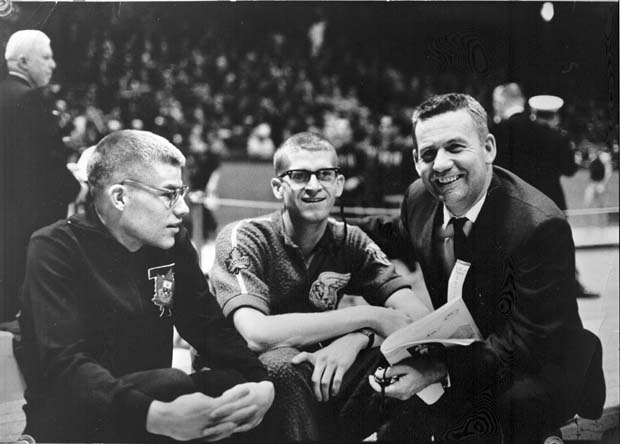

While Kidd the student was beginning this academic progress, Kidd the runner was spoiling Murray Halberg’s sleep.

While Kidd the student was beginning this academic progress, Kidd the runner was spoiling Murray Halberg’s sleep.

“Every morning for a year, the alarm went off at 6:30. Every morning, the Halberg hand would grope out and kill the nerve-jangling racket and the thought would flash… ‘Bruce Kidd.’” That’s Halberg, New Zealand’s Lydiard-coached 1960 Olympic 5,000m gold medallist, 1958 Empire Games three-mile champion, five times the world’s top-ranked 5,000m runner, writing in A Clean Pair of Heels (1963). Halberg detested that alarm clock because it was only a third-place prize, from the Compton Relays 5,000m in Los Angeles in 1962. Every morning, it reminded him that a Canadian teenager he had seriously

underestimated had outraced him, inf licting Halberg’s first international defeat at three miles. Every morning, the clock’s “Brrrrrrrrrruce-Kiddddd” clatter drove Halberg out to train for their next encounter.

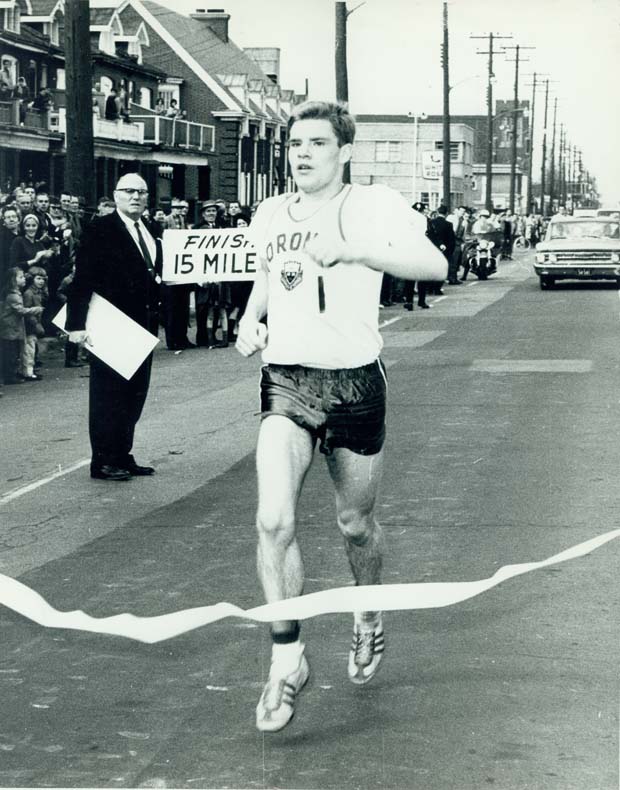

“Kidd is a most astute character, who had beaten me at my own game. He has a distinctive high-stepping, toey action with a high arm carriage and peculiar f lick or throw of the arms. I must admit he can get along like that,” Halberg comments. Kidd’s stride seemed prancing, and he habitually propelled his long finishing burst with a kind of low-scooping movement of the arms, hands downward. “Dog-paddling Bruce Kidd,” the reluctantly admiring British tabloids labelled him. His signature tactic was to break away two or more laps from the finish. That was also how Halberg won in Rome, but it was rare enough to have surprise value.

It served Kidd well in the Empire Game’s six-mile event that hot day in Perth in 1962, his most significant race. The field was not far off Olympic quality. Dave Power (Australia)

and John Merriman (Wales), who took silver and bronze behind Kidd, had placed third and eighth in the 1960 Olympic 10,000m. Barry Magee (New Zealand), fourth, was the 1960 Olympic marathon bronze medallist. Roy Fowler (England), ninth, won bronze in the 1962 European 10,000m. The soon-to-be great Kipchoge Keino (Kenya) was way back, with Kenya’s number one, Arere Arentia. Fifth was Kidd’s personal hero, England’s Martin Hyman, prominent in Britain’s campaign for nuclear disarmament and anti-apartheid movement, whom Kidd still deeply admires for his combination of high-level sport with idealistic activism.

Kidd beat them all.

He nearly did it again two days later in the three miles, another hot day and hot field. At the bell, Kidd was leading, arms scooping, pressing to break away again, despite having had only 48 hours to recover from that boiler-house six miles. But the canny Halberg was tailing him.

“I’d not expected him to start only two days after the six… but this boy Kidd is something different. For 11 laps, wherever Bruce Kidd was in the field, I was right there…poised just behind his right shoulder,” Halberg wrote. On the last lap, Halberg “threw [himself ] forward and [he] was away.”

Australia’s Ron Clarke (who had dropped out of the six miles) also got by Kidd. For the bronze medal, Kidd beat European champion Bruce Tulloh, fourth, Albie Thomas (Australia), fifth, and former world mile record-holder Derek Ibbotson (England), eighth, all fresh, plus Arentia and Keino again.

Three days later, he rashly decided to run the marathon. It was a cool day, but his longest prior race was 15 miles, and he was coming off two peak track races. Suffering, he dropped out after 25k.

His two Perth medals against such competition made him a favourite for the Tokyo Olympics in 1964. But the best was over. He still won major races, like the British indoor two-mile championship early in 1964, but he raced too often and trained without respite. The intensity was coming now from desperation.

“I didn’t have enough respect for the rest phase of the stress-to-rest cycle. Fred Foot would agree. Effectively I raced every day,” Kidd said this year. My ankle was painful, and I was living on anti-inflammatories. Eventually I had two bouts of surgery. When I was struggling for form in 1963–64, stupidly I thought I had to work even harder. I did monster workouts. I was tired all the time.”

He fulfilled his boyhood ambition, but becoming an Olympian brought only misery. In the 10,000m he was 26th, fourth from last, lapped twice by the leaders, and in the 5,000m he was ninth in his heat. In both, he was minutes slower than at Perth.

If Tokyo was the first day of the rest of his life, Kidd fortunately had more things available. “Sport was good preparation for my career. I’m so glad I came of age through running. It gave purpose and focus in navigating the shoals of adolescence. I had great help from my coach and training partners. Running introduced me to the world. Sport is an extraordinary lesson in geography and history,” he said.

Sport was also a lesson in injustices, such as the mistreatment of black and female athletes. “My friendships with Harry Jerome and Abby Hoffman pulled the wool from my eyes about the extent of racism and gender discrimination in North American sport,” he told Christopher Kelsall for the website Athletics Illustrated.

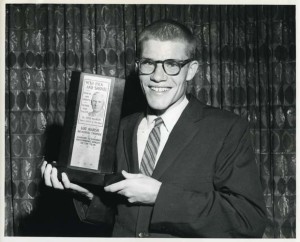

So he began to give back, by what he calls “critical support for sport.” That’s the title of his latest book (2013). It often took the same reckless self-belief as going up against Halberg and Clarke. When Kidd was given the Ontario Sportswriters Athlete of the Year Award in 1963 (still aged only 19), he took the opportunity to criticize violence in hockey, sport’s culture of cheating and gambling, the exploitation of amateur athletes, and other shortcomings. That speech was received in near silence, and he was subjected later to cold shoulders and physical threats. Only Kiwi Murray Halberg, who was present, publicly stood by Kidd.

He persisted in being a dedicated but critical supporter of sport. As a volunteer administrator, he led Canada’s first team to the World Student Games, while advocating for full student participation in the organization, as well as the involvement of women. He campaigned against South Africa’s apartheid. He worked hard for the 1976 Montreal Olympics but joined protests against Mayor Drapeau, “believing his ‘law and order’ agenda undermined the humanitarian goals of the Olympic Movement.” At the 1988 Winter Olympics in Calgary, he demonstrated for the resolution of First Nations land claims.

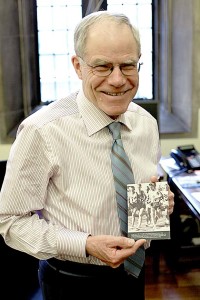

He also took up running again, for the sheer love of it. “I ran well at a national level, but I couldn’t sustain the old workouts. It took a while to get used to not winning, and there were times when I was immersed in something else. But those later years of running gave my happiest moments. I discovered that I love running and racing so much, just going out and bashing it. I had a lot of fun using my race knowledge.” But in the end injuries stopped him. His last race was the Helsinki Marathon in 1982.

“Having fun” is how Kidd also describes his work as university principal. He is far from being earnest or self-righteous. He has a ready smile, and an engaging warmth and vitality. He enjoys supporting his wife Phyllis Berck at masters races. They met through the Calgary Winter Olympics. He bikes with vigour. He advocates against “sedentary death syndrome.” (No chance in his case.) He describes himself as “a deeply patriotic Canadian.” “That was a long journey. Representing my country made me think about what it was about,” Kidd reflects. “I realized that I needed to take some responsibility for it – that grew over the years.”

At the end of our last conversation, I asked Kidd to apply his mindset of “critical support” to today’s booming mass running culture. He thought for a moment. “Terrific things are happening,” he said. “I never expected the huge numbers of mature women who are running. The social and health benefits are immeasurable.” But Kidd still applies his critical approach. “Two things trouble me: distance running has become wholly a road sport. Even the top runners don’t think about racing on the track, and that’s a loss.”

Secondly, the commercialization, the in-your-face entrepreneurialism, troubles Kidd. “It saddens me that races are private corporations, for profit. There’s no co-ordination. Conflicts come from entrepreneur’s desires,” Kidd feels. “They use public streets and services, and we’re entitled to an overarching democratically elected body, as there is in Switzerland, to oversee the race calendar and demand accountability, to the public, to the runners, and to the city.”

To invite Bruce Kidd at 71 to offer a critical opinion is like reaching two laps to go in a race when he was 17. Brace yourself.