Recalibrating carbon-plated running performances

A look at how much time savings could come from a pair of shoes

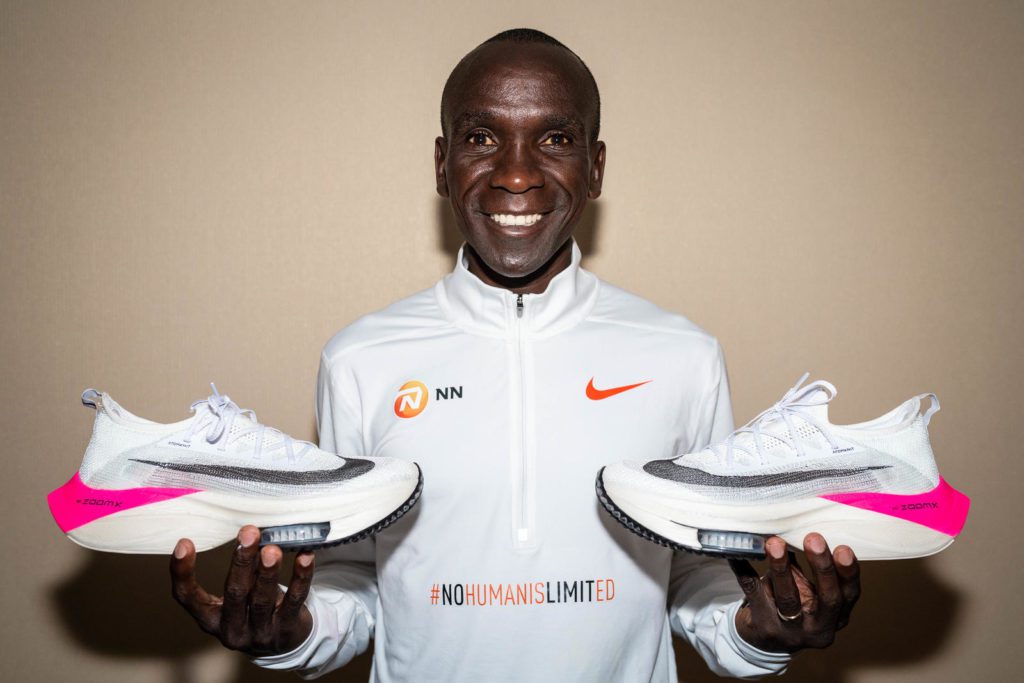

For the past three years, various iterations of Nike carbon-plated shoes have been causing controversy. They’ve gone from exciting to rule-breaking and back dozens of times, with each version faster and more exclusive than the one before it. The flurry of running records broken in the past three weeks and the Nike Next% (the commercial version of the shoe that helped those records happen) is a topic of conversation once more.

RELATED: Kipchoge’s shoes spark backlash

On October 12, Eliud Kipchoge ran 1:59:40 for the marathon. One day later, Brigid Kosgei shattered the women’s marathon record, running 2:14:04, a time that was previously almost inconceivable for a woman. Both of these runners are the cream of the crop, and likely the fastest of their generation–but both runners were also wearing a Nike shoe, “the” shoe.

A new era in the marathon, ushered in by shoe tech. In our latest podcast, we explore the “recalibration” of running performances (2:03 is the new 2:05, 2:15 the new 2:18), integrity & fairness, how the tech works, and what should be done about it: https://t.co/alXIIaJyGu

— Ross Tucker (@Scienceofsport) October 24, 2019

Dr. Ross Tucker is an exercise physiologist with an interest in this shoe. He’s a regular on the Science of Sport Podcast and on this week’s episode addressed the topic, referring to it as the shoe that broke running. Tucker said on the podcast, “I wouldn’t hesitate to use the term mechanical doping. I’m not accusing the athletes who are running of cheating, but those mechanical advantages are enormous.”

Tucker explains that the shoe doesn’t make a person four per cent faster, but what it can do is improve their running economy by four per cent, resulting in a range of faster times. While the gains in efficiency aren’t equal across the board, Tucker feels that this shoe isn’t making anyone worse, and beyond that, it’s probably making people significantly better. “We might not be able to pin down exactly how much [Eliud] Kipchoge or [Brigid] Kosgei or [Kenenisa] Bekele are getting. It might not be four per cent, but it’s not zero. This shoe gives an advantage physiologically that translates into a performance advantage. And it’s worth minutes for some athletes, it could be worth four to five minutes for some runners.”

He continues to say that there have been studies that suggest that a four per cent energy savings over the course of a marathon is worth a 2.7 per cent performance benefit to an elite marathon runner. If we’re operating on the assumption that 2.7 per cent is the upper end of time savings in these performances, then Kipchoge and Kosgei’s times are no longer that ground breaking–they’re strong runs, but not an enormous leap forward.

RELATED: 8 of 12 fastest marathons in history have been run in the past year

#PVFPB

After Kipchoge and Kosgei’s record-shattering weekends, there was a new hashtag floating around on Twitter: #PVFPB. This acronym refers to a runner’s pre-Vaporfly personal best (Nike’s original commercially available carbon-plated shoe).

For example, Kipchoge’s winning time at Berlin 2015 was a 2:04:00, when he wasn’t wearing carbon-plated shoes (admittedly, he did have a shoe malfunction in 2015 which you can read about here.) He won and set the world record on the same course in 2018 in 2:01:39, a time that’s 2.4 per cent faster.

If you’ve recently run a marathon in a carbon-plated shoe, check out how much you improved compared to non-carbon-plated races. There are so many variables that go into a personal best, but if your lead up was similar to previous builds but your time is roughly 2.7 per cent better, it could be the shoe. This metric was developed with the elite marathoner in mind, but if you’re curious about what your energy savings might look like in time, this is a good place to start.