The mega-distance aliens of years gone by

The author of a new book about Al Howie, who in 1991 ran across Canada faster than anyone before or since, introduces us to a world of mega-distance running that has all but disappeared

by Jared Beasley

Jared Beasley is the author of a new book about one of Canada’s most gifted ultrarunners, In Search of Al Howie. He lives in New York.

Ultrarunning and trail running are now one and the same–but, should they be?

Brutal runs into mountains and deserts have flowered over the last 20 years, sparking our imaginations with steep, foreboding cliffs and what seem like inhuman distances. But ultrarunning didn’t begin on dirt, but on tracks and asphalt. Beneath the dust of 100-mile mountain runs and the suffocating speed of the digital age lies buried a golden age of ultras with distances so unthinkable, they are alien to even our modern-day champions. If the Moab 240 is as foreign to the marathon as golf is to cricket, then what the vagabond ultrarunners of the ’80s were doing was a different sport altogether. They were doing mega-distance.

RELATED: 10 of Al Howie’s most mind-boggling achievements in ultrarunning

Disclaimer: I love Joe Rogan, and Courtney is a true badass. It’s 2017, and Joe asks ultrarunning phenom, Courtney Dauwalter, “238 miles? That’s got to be the longest anyone has ever run?” She giggles and shrugs her shoulders. “No, really,” says Rogan. His assistant Jamie pops up the 3,100-mile Sri Chinmoy race in Queens. Rogan squints at the screen. “That must be a relay race.” Courtney adds, “Well, I’ve heard of six-day races.” Similarly, Rich Roll, an ultrarunner himself and a podcaster known for doing his homework, asks Run and Become director Sanjay Rawal, “who was Ted Corbitt?”

When stumbled upon, mega-distance pioneers come off like characters from the Old Testament–unusual names with extremely long numbers attached. Yiannis Kouros is one relic who still chimes bells in the back of some ultra-trailrunning minds. Between 24-hour races and 1,000 miles, no one could touch him. Some of his records: six days–644 miles. 163 on the first day. The 24-hour race–188 miles. The 48-hour race–294 miles. In the infamous “Westfield Sydney to Melbourne” race, the only ultra to put up serious prize money (the winner got $20,000 in their pockets), Kouros ran the hilly 544-mile distance in five days, second place finishing an entire day behind. Two years later, the organizers would pay him to give the rest of the field an eight-hour head start. He still won… by 12 hours.

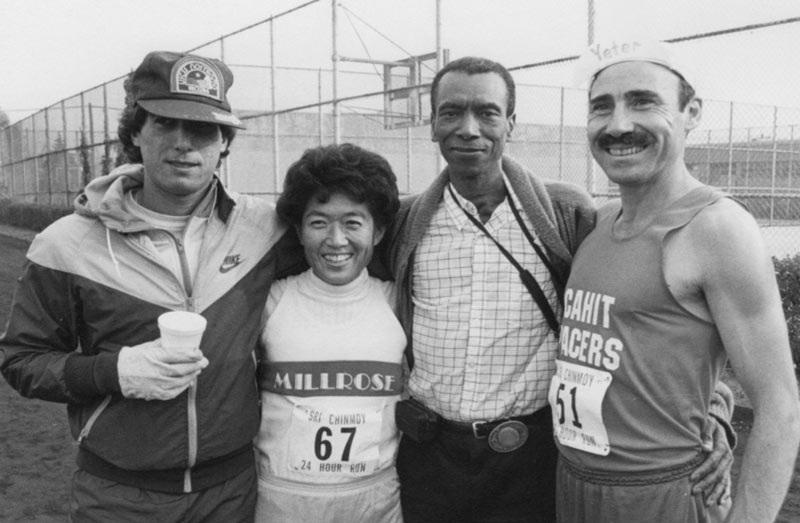

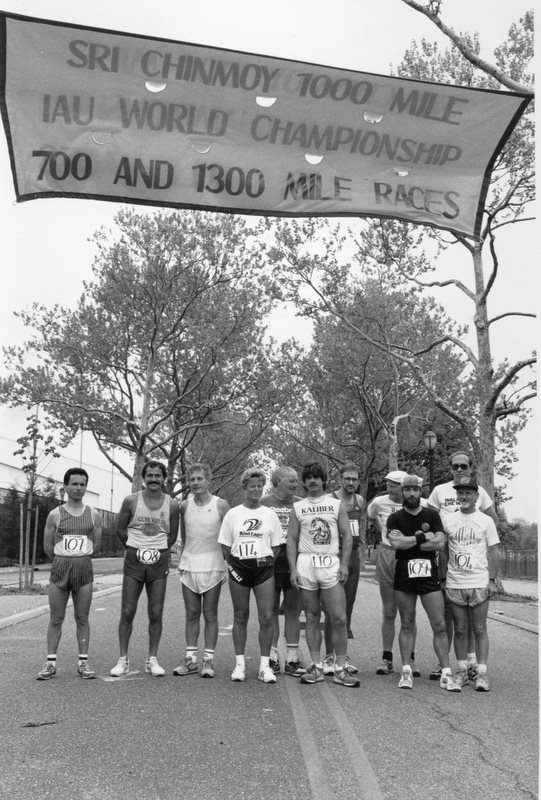

A thousand miles and beyond was the domain of Al Howie, a completely covered-over artifact of this lost breed of athlete. In 1989, Howie showed up at the Sri Chinmoy 1,300-mile race. Dubbed “The Impossibility” race, at the time it was the longest certified race in the world–2,092 kilometres. Trishul Cherns, the Canadian ultrarunner and three-time finisher of the recently-documented 3,100-mile race, says the 1,300 was clearly the toughest ultra he has ever seen. Why? It had an 18-day cutoff.

The first two years it was run, no one could finish it. Any runner who dared it would have to average over three marathons a day around a mundane one-mile loop to beat the cutoff. Frank Shorter called it “physically impossible.” But Al Howie did just that, burning the first marathon in under three hours and putting 123 miles in the books the first day. Seventeen days and nine hours later, Howie crushed the “impossible.” On top of that, he did it in Ron Hill 2.07 flats, what even hard-boiled runners called glorified “ballet slippers.” Fast-forward two years, and Howie runs across Canada in 72 days 10 hours, the fastest man ever to attempt it. Two weeks after that, he shows up again at the 1,300 and destroys his own record by 14 hours, running 1,300 miles in 16 days, 19 hours. In total, Howie had run 5,800 miles in 103 days. That equates to 9,335 kilometres–221 marathons–or the distance as the crow flies from Vancouver to Bolivia.

Those are but two of the “terracotta army” of radical runners lost in time from the golden age of multi-day, mega-distance running. There were scores: Don Ritchie, Phil Latulippe, Don Choi, Sandy Barwick and Dipali Cunningham. Distant cousins, technology removed, they shared a fanatical family trait with the Jureks and Dauwalters (extreme running), but resided on opposite ends of the distance menu. They cut toe-boxes, removed toenails, and crossed continents. And while trails are alive, thriving, and more accessible, multi-days are facing extinction, disappearing into the often opaque ground of the past. In the age of handheld supercomputers and instant gratification, they make no sense. But the souls who dared them remain the essence of myth itself, the great white whales of Melville’s day: “extraordinary creatures which the mutations of the globe have blotted out of existence.”

These “aliens” strove to answer one simple, elemental question: how far can you run?