Why am I so willing to dismiss the pain? Just days after pounding out another 42.2K on hard, unforgiving pavement, why did I now itch to get back out there? Why, when I couldn’t even walk properly — strides disjointed and stiff, bolts of pain firing up and down my legs– did seeing other people running hurt even more?

A very, very small fragment of the population will ever finish a marathon. In the U.S., it’s estimated to be one in 200, or a half of one per cent. Obviously a remarkable amount of dedication, focus, sacrifice and suffering occurs before anyone gets to say they did a marathon. It’s a hell of an accomplishment just to do one.

Pelted by snow, worried I’d piss myself (or worse), leg muscles like restless pythons writhing under my skin.

This time last year, when I finished my first, I wouldn’t allow myself to say I was a marathoner. I was deservedly proud of myself, content with my time, thrilled I fought through the entire course without having to walk any of it. Pelted by snow, worried I’d piss myself (or worse), leg muscles like restless pythons writhing under my skin. It was a terrible, but utterly satisfying experience.

Afterwards, my lips were blue and it took me more than an hour to stop shivering. A week later, my reserves depleted, I spent two days pasted to the couch, barely able to lift my head.

I rode that high – and it was a high – for weeks, but I wouldn’t call myself a marathoner.

To me, a marathoner isn’t someone who ran a marathon. It’s one who does marathons; someone who knows before they finish this race, how they’ll prepare differently for the next… because there will be a next.

I still hold on to the memory of a popular girl chatting with me while her popular girl friend stood behind me, dropping spit in my hair.

At this point in my life, I need to be a marathoner. Physically, I’ve come a long way in a short amount of time and I know how easily I could slide back into being the fat kid I’ve felt like for most of my adult life. It has taken me this long to shake that self image..

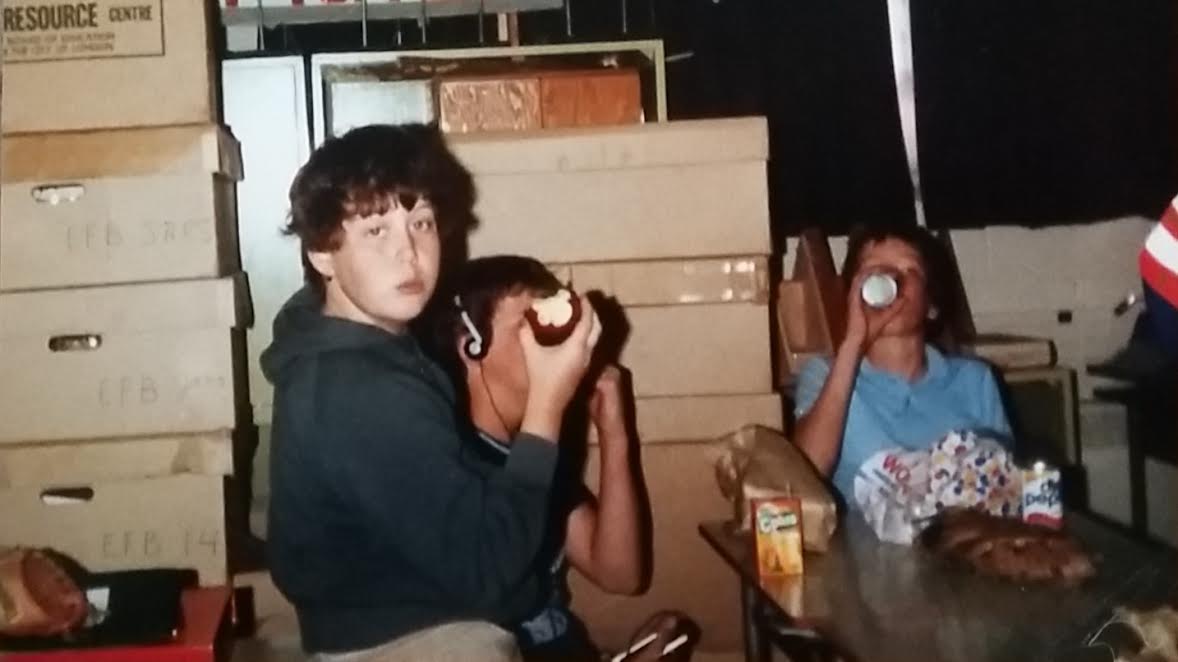

In elementary school, junior high and high school I was bullied. I still hold on to the memory of a popular girl chatting with me while her popular girl friend stood behind me, dropping spit in my hair. I remember getting shoved in the hallways, tagged with unflattering nicknames and having money stolen by kids who knew I wouldn’t tell on them. I was fat, I wasn’t stupid.

Other kids had it far worse than me. Last year, at the Scotiabank Toronto Waterfront Marathon Runner’s Expo, I heard Jean-Paul Bédard explain that he’s able to run for hours a day, every day, because – as a survivor of childhood sexual abuse – he’s used to coping with a much stronger pain.

Calling myself a marathoner isn’t just about saying I’ve done 42.2K, it’s about knowing I can do 42.2K. It’s knowing the discomfort is of my own making; that my physical, mental and emotional wellbeing are hinged to what I’m willing to endure.

A day after my most recent marathon, I could barely make it down stairs without clutching at the walls, and even then, it was gnawing at me that I wasn’t outside running. The soreness I invite – burning muscles and dull aches that nag at me for days following each long run – is a recurring reminder of what I’m willing to tolerate so that I can progress.

It’s about proving to myself again and again that I’m no longer the traumatized 14-year-old that faked being sick for a month of grade nine.

It’s not about being thin. Runners come in all shapes and sizes. It’s about proving to myself again and again that I’m no longer the traumatized 14-year-old that faked being sick for a month of grade nine.

I never set out to do marathons. I figured I would do one, then move on to something else. But getting that first one done triggered something in me. Something changed when I crossed that finish line in October of 2015. That’s when I knew, despite the all the punishment it would involve, that it wouldn’t be enough to say “I did a marathon.” I was going be a marathoner.