Why you shouldn’t aim for 180 steps per minute

Contrary to popular belief, there's no magic stride rate that works at all speeds.

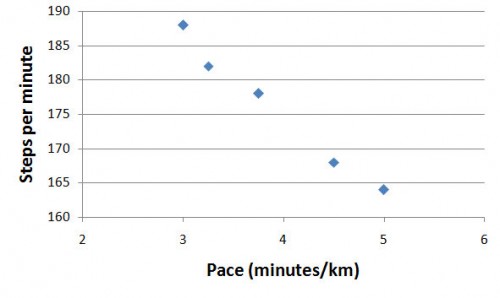

My wife is out of town at the moment, which means I’m doing lots of running on my own. Plenty of time to ponder the meaning of life — and, when I get tired of that, to count my footsteps. Sparked by interesting discussions with the likes of Pete Larson from Runblogger and Dave Munger from Science-Based Running, I’ve been wondering what my own cadence is like — particularly in light of widespread belief in the magic of 180 strides per minute. Over the past few weeks, I counted strides for 60-second intervals at a variety of paces. Here’s what I found:

Most surprising to me was (a) how consistent my cadence was when I repeated measurements at the same pace, and (b) how much it changed between paces: from 164 to 188, with every indication that it would decrease further at slower paces and increase further at faster paces. This certainly confirms what Max Donelan, the inventor of a “cruise control” device for runners that adjusts speed by changing your cadence, told me earlier this year: contrary to the myth that cadence stays relatively constant at different speeds, most runners control their speed through a combination of cadence and stride length.

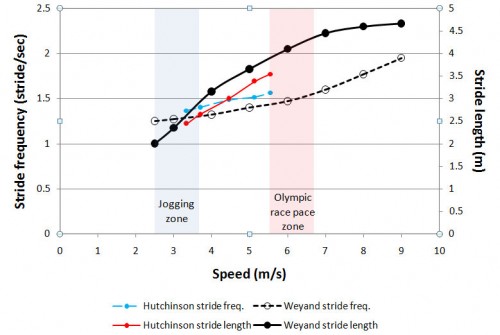

So the next question is: am I a freak, running with a “bad” slow cadence at slower paces, but a “good” quick cadence at faster paces? To find out, I plotted my data on top of the data from one of the classic papers on this topic, by Peter Weyand:

The graph is a little busy, but if you look closely, you’ll find that my data is slightly offset from the Weyand data, but has essentially identical slope. So compared to Weyand’s subjects, I have a slightly quicker cadence and shorter stride at any given speed, but my stride changes in exactly the same way as I accelerate. So I’m not a freak: the fact that my cadence increased from 164 to 188 as I accerelated from 5:00/km to 3:00/km is exactly consistent with what Weyand observed.

One key point: I’ve highlighted two key “speed zones.” One is the pace at which typical Olympic distance races from the 1,500 metres to the marathon are run at. This is where Jack Daniels made his famous observations that elite runners all seemed to run at 180 steps per minute (which corresponds to 1.5 strides per second on the left axis). The other zone is what I’ve called, tongue-in-cheek, the “jogging zone,” ranging from about 4:30 to 7:00 per kilometre. This latter zone is where most of us spend most of our time. So does it really make sense to take a bunch of measurements in the Olympic zone, and from that deduce the “optimal stride rate” for the jogging zone?

This isn’t just a question of “Don’t try to do what the elites do.” If Daniels or anyone else had measured my cadence during a race, it would have been well above 180. But at jogging paces, it’s in the 160s. I strongly suspect the same is true for most elite runners: just because we can videotape them running at 180 steps per minute during the Boston Marathon doesn’t mean that they have the same cadence during their warm-up jog. In fact, that’s a pretty good challenge: can anyone find some decent video footage of Kenyan runners during one of their famously slow pre-race warm-up shuffles? I’d love to get some cadence data from that!

Of course, this doesn’t mean I don’t think stride rate is important. I definitely agree with those who suggest that overstriding is probably the most widespread and easily addressed problem among recreational runners. But rather than aspiring to a magical 180 threshold, I agree with Wisconsin researcher Bryan Heiderscheit, whose studies suggest that increasing your cadence by 5-10% (if you suspect you may be overstriding) is the way to go.