Canada’s greatest Olympics: what really happened in 1928

In this excerpt from his new book, Running Throughout Time: the Greatest Running Stories Ever Told, Roger Robinson explains how what started as an exhibition of women's weakness became a demonstration of men's dishonesty and prejudice

Canada one time made Olympic history that was both splendid and shameful. It was the 1928 Games in Amsterdam, the first when women were admitted to the track and field program. Canadian women were key to what ensued, in an event that has been notorious for almost 100 years–and has been seriously misreported and misunderstood for almost all that time.

I uncovered the whole confused story for my new book, Running Throughout Time: the Greatest Running Stories Ever Told. It was a research project that became more like a crime mystery novel. Facts and culprits kept changing. What started as an exhibition of women’s weakness became a demonstration of men’s dishonesty and prejudice.

The women’s 800m at those Games–the first high-level middle distance track race ever for women–was taken at the time as evidence that women are not suited to such tests of endurance. The world’s media united in condemning the spectacle of “wretched women,” “prostrate and distressed,” collapsing exhausted around the track and sobbing at the finish line. Five of the 11 women collapsed, and five dropped out without even reaching the finish line, wrote one reporter, aware that exact stats make the most convincing journalism.

In fact, those numbers are evidence of the flagrant dishonesty of the sports journalism profession at those Games. They misreported the race in every way. The stories of mass collapse and distress, amazingly consistent across many international news reports, were fake news, hugely exaggerated, often grossly inaccurate. There were nine women in the race, not 11. None failed to finish. Four or five fell to the grass at the finish, yes, but they had just run massive personal bests; two were sprinters racing their first big 800.

Even the film footage that we all know (in documentaries like Free to Run or Spirit of the Marathon) proved to be misleading, phony evidence. I will say here only that you are not watching what you think you are watching.

The litany of lies concealed the truth that the race was a great leap forward in women’s running. The first three broke the recent world record, and the first seven (yes, seven) ran faster than the officially ratified world mark at that date, including two Canadians. That race deserves a revised place in history, not as evidence of women’s weakness, but as a major breakthrough in elite athletic performance.

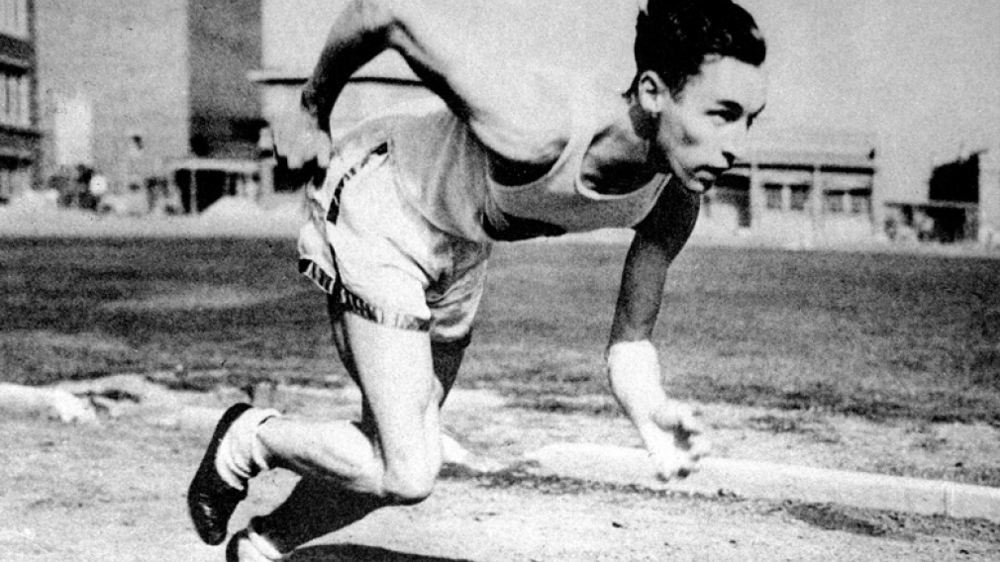

The two Canadians were in the thick of it. Fourth in the final field of nine was 17-year-old Jean (Jenny) Thomson, from Penetanguishene, Ont., in a huge personal best 2:21.6. Fifth (2:22.4) was the talented all-rounder Fanny (Bobbie) Rosenfeld (far right in the photo above), from Toronto. Also a hockey star, Rosenfeld had already won the silver medal in the 100m, and went on the be part of Canada’s world-record breaking gold medal 4 x 100 relay team.

Rosenfeld’s medals helped Canada finish the Amsterdam Games as the top women’s track and field team in the medal count. Ethel Catherwood (Regina) won the high jump in a world record, and Ethel Smith (Toronto) took bronze in the 100m, for a total of two gold, two silver, and one bronze, from only five events. Or five gold medals, if you count the relay as four. Canada’s men also did well, thanks to two sprint golds by Percy Williams (Vancouver), gaining four in all. It was probably Canada’s best track Olympics, edging 1932 (11 medals, but only one gold), thanks largely to the women.

The shame, and the mystery: a week later, Canada led the move to cut all women’s track and field events from the Olympic program. The Canadian delegates actually put that motion. Why? When Canada’s own women had performed so well? It happened at the special international meeting held to decide the future of the women’s Olympic program, when the air was steamy-hot with all the sensationalized sexist misreporting of the 800m (“the gals dropped in swooning heaps as if riddled by machine gun fire”), and every journalist was calling (surely not by coincidence) for that event to be banned. The 800m was cut from future Olympics by a vote of 12-9. The remaining four women’s events were saved by a 16-6 vote. Canada voted for exclusion both times.

Why did Canada betray its own medal-winning women? Envy? Male delegates resentful because the women outshone the men? Politicking against the rising strength of women’s sport? Rivalry between federations? Plain backward sexism by old fuddy-duddies? At this distance, we’ll never know. But coming so soon after Canada’s women proved themselves such a force, leading that negative vote was not Canada’s proudest Olympic moment.

By the way, the legendary Paavo Nurmi also fell exhausted to the grass at the finish line in those Games. No one called for the men’s 5,000m to be banned.

The extraordinary story of the 1928 Olympic women’s 800m is one of 14 great stories told (with revisionist new research) in Roger Robinson’s Running Throughout Time: the Greatest Running Stories Ever Told (Meyer & Meyer, 2022), $24 from bookstores and all online suppliers. Based in New Zealand and New York, Roger has written frequently for Canadian Running.