The carbon shoe revolution

How the new carbon-plated shoes are changing the running game

By Alex Hutchinson

Strictly by the numbers – and when you’re talking about running, what else is there? – you can make a pretty good case that last fall’s Scotiabank Toronto Waterfront Marathon was the greatest day of marathoning in Canadian history. Kenyan stars Philemon Rono and Magdalyne Masai-Robertson notched the fastest times ever on Canadian soil. The top Canadians, Trevor Hofbauer and Dayna Pidhoresky, both slashed about seven minutes off their previous bests to clinch spots on the Tokyo Olympic team. In all, an unprecedented nine Canadian men broke 2:20 and five Canadian women ran under 2:37, capping what long-time running statistician Maurice Wilson calls “without question, the best year ever for Canadian marathoning.”

Numbers don’t always tell the whole story, though. All these boundary-pushing runners have a lot in common – years of arduous training, a voracious appetite for suffering, muscle cells packed with mitochondria – traits shared by generation after generation of marathoners. But the top finishers in Toronto also shared something newer: an efficiency-boosting carbon-fibre plate embedded in the midsole of their shoes.

Back in 2017, when Nike introduced the Vaporfly, a shoe featuring a full-length, spoon-curved carbon plate, few fathomed what a game-changer the innovation would prove to be. Then Vaporfly-wearing athletes starting winning races and breaking records – including both the men’s and women’s world marathon records – at an astonishing rate. Rono, Masai-Robertson, Pidhoresky and Hofbauer were all wearing versions of the Vaporfly in Toronto. By that point Nike’s shoe had become so dominant that the biggest surprise was that some of the top finishers weren’t wearing it. Among the sub-2:20 contingent, Cam Levins and Rory Linkletter were in Hokas; Reid Coolsaet and Chris Balestrini were in New Balance – all with their own carbon plates.

In a sense, the results in Toronto marked an inflection point. For two years, Nike’s carbon plates were at the centre of a vigorous debate about fairness and technology in sport, largely because no one else had them. But the competition has arrived: nearly every major running shoe company will have a carbon-plate shoe on the market in 2020. And thanks to the near-deafening chorus of praise from early adopters – not just how fast the new breed of shoes are, but how great your legs feel even after a long run – they’re no longer aimed only at would-be Olympic marathoners. Shoe companies are betting big that this will be the year we all sign up for the carbon revolution.

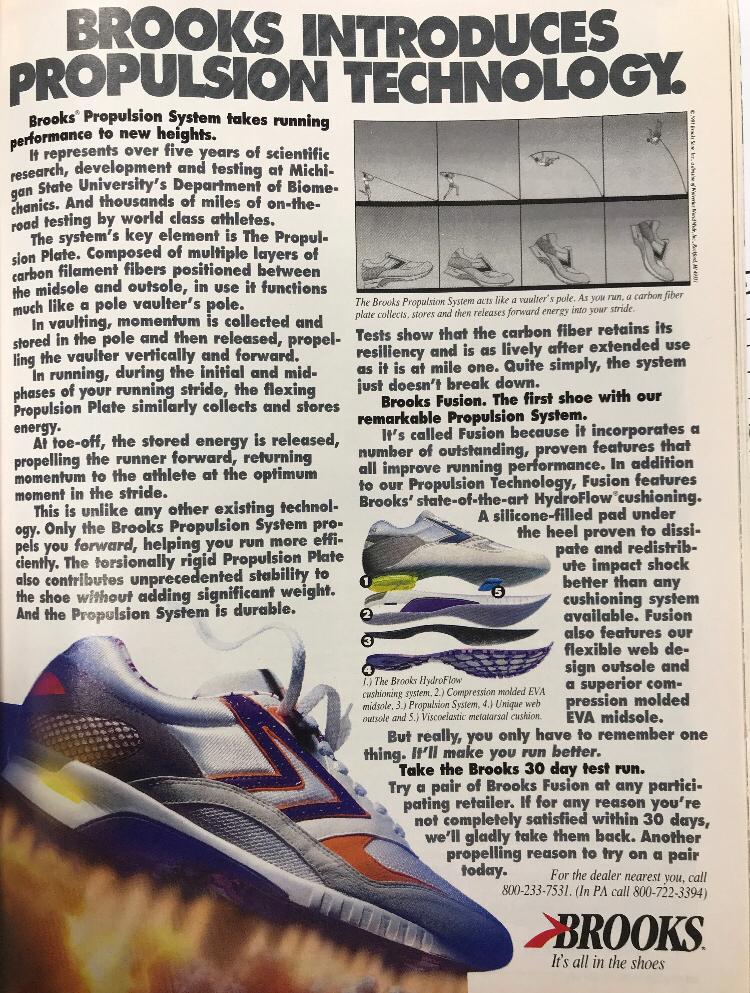

The idea of sticking a rigid carbon-fibre insole into a running shoe might seem like a bizarre and novel idea. But like most revolutions, this one was simmering for a long time before it blew up. As far back as the 1980s, shoe companies were playing around with the unique combination of strength and light weight offered by carbon fibre. Around 1989, Brooks launched a pair of shoes – the Fusion and the Fission – that incorporated the technology. “The Brooks Fusion had a carbon-fibre plate sandwiched between the midsole and outsole that functioned as a propulsion system,” recalls Nikhil Jain, the senior manager of Brooks’ high-performance line.

Other companies like Fila also produced racing shoes with carbon-fibre plates in the 1990s, but the next big leap was taken by scientists at the University of Calgary’s famed Human Performance Lab, working with Adidas. A young mechanical engineer named Darren Stefanyshyn developed a curved plate design that, according to data later published in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, improved running economy by an average of one per cent. Running economy is a measure of efficiency, meaning that you’d be able to sustain a given running speed while burning one per cent less energy – which should, in theory, translate directly to faster race times. Adidas dubbed it the ProPlate and incorporated it into some of their shoes in the early 2000s (including, according to the Adidas website, the shoe used by Ethiopian great Haile Gebrselassie to set a world marathon record in 2007). But the somewhat abstract concept of a marginal improvement in running economy never really captured the public’s imagination, and Adidas quietly scrapped the shoe.

Then came Nike – and for their new shoe in 2017, they took a dramatically different approach to getting the world’s attention. It would have been easy to put out a few press releases hyping up the Vaporfly’s groundbreaking features, boasting of its performance in in-house testing, and listing all the gold medalists who were already wearing it. That’s what shoe companies do pretty much every spring, and most of us instinctively tune out the hype. Instead, Nike made a risky bet: they announced that three of their star runners would attempt to run a marathon-distance exhibition race in under two hours, and that their new shoe, featuring a carbon-fibre plate, would help the runners do it.

Given that the world record at the time was nearly three minutes slower than the sub-two goal, most pundits foresaw a lose-lose scenario for Nike: if the race flopped, it would prove the Vaporfly was no good; if it succeeded, it would prove the shoe was cheating. As it turned out, in May 2017, the reigning Olympic champion, Eliud Kipchoge, raced to a sizzling (but unofficial) 2:00:25 at the Breaking2 race at a Formula One track in Monza, Italy. It was close enough to sub-two that critics immediately called for the shoe to be banned. But the detractors soon ran into a problem: no one could agree on what exactly the plate in the shoe was doing, much less why it should be banned.

Stefanyshyn, in his work with the ProPlate, had suggested that the magic of the carbon-fibre plate was that it kept your big toe joint straighter during toe-off, saving energy that would otherwise be wasted in bending the joint. But the savings seemed to come at a cost, putting additional strain on the ankle joint. Nike’s Vaporfly design team was led by a researcher named Geng Luo – who, crucially, had completed his PhD in biomechanics at the University of Calgary in 2012, supervised by none other than Darren Stefanyshyn. Luo and his colleagues introduced a jauntier curve to the plate, which seemed to reduce the extra load on the ankle. But the plate’s genealogy was clear, making it hard to argue that Nike’s shoe was somehow breaking the rules in a way that the previous plate-equipped shoes from Adidas, Fila, Brooks and others hadn’t.

And the plate, it turns out, was only part of the story. While previous marathon racing shoes have erred on the side of minimalism, the Vaporfly sat on a chunky 31-mm-thick foam midsole made of a new material Nike dubbed ZoomX. All running-shoe midsoles, in addition to providing cushioning, function as a sort of spring. They compress when you land, and spring back as your foot takes off, giving a little jolt of free energy. The vast majority of midsoles use ethylene vinyl acetate, or EVA, which typically springs back with at most about 65 per cent of the energy you put into them. Adidas’s groundbreaking Boost midsoles, which use a thermoplastic elastomer called TPU, got 75.9 per cent in a 2017 University of Colorado study. The new ZoomX foam, which is made from another thermoplastic elastomer called polyether block amide (PEBA), returned a jaunty 87 per cent.

As well as being more resilient, ZoomX is also way lighter than EVA, which is why the Vaporfly can have such a thick midsole without becoming unreasonably heavy. The thick midsole allows it to store more energy with each footstrike, like having a bigger battery in your shoe, and the higher resilience gives you more of that energy back. A simple and underappreciated benefit of the carbon plate may be that it keeps the unusually thick and soft midsole stable, so that you don’t feel like you’re running with a pair of giant marshmallows strapped to your feet. The overall result of combining the plate and the foam is that Nike’s original Vaporfly, according to testing at several different universities, improves your running economy by a staggering four per cent on average compared to the next-best racing shoes. That seems to translate to an improvement of somewhere between two and four per cent for race times – or between three and seven “free” minutes for a three-hour marathoner.

At this point, the only thing we can say for sure is that no one truly knows exactly how or why the combination of plate and foam works so well. “There’s a lot of storytelling or myths around these carbon-plate shoes,” admits Spencer White, Saucony’s VP of innovation. That’s one of the reasons it has taken so long for rival companies to launch Vaporfly competitors. Elite runners from almost every company have been racing in unreleased prototypes for several years now. For example, Des Linden won a rain-soaked Boston Marathon way back in April 2018 in an early prototype of Brooks’ Hyperion Elite; the shoe, featuring a carbon-fibre plate embedded in a thick layer of the company’s new DNA ZERO foam, will finally come to market in Canada this fall, after two and a half years of tweaks and redesigns. The goal of the plate, according to Jain, is to stabilize the foam and “provide that snappy feel and propulsion at toe-off.”

Other companies have their own takes. In Saucony’s new Endorphin Pro shoe, White says the carbon-fibre plate plays two roles: spreading the force of your heel’s landing impact out into a new ultralight, ultraresilient foam made from the same type of material as Nike’s ZoomX; and rolling your foot forward while keeping the toe joint straight. In Under Armour’s HOVR Machina, according to the Ben Schoonover, the company’s director of run footwear, a carbon composite plate is designed to “make the transition off the forefoot feel snappier.” Meanwhile, New Balance’s FuelCell TC, again featuring a carbon-fibre plate and a new ultra-resilient foam, aims to provide a “combination of energy return and protection from eccentric loading” in runs lasting longer than an hour, according to Dave Korell, the company’s manager for performance shoes in Canada.

That last point – protection from eccentric loading – may seem like an afterthought, but it could turn out to be the make-or-break feature for the whole category of shoes. Eccentric loading is the braking action of your leg muscles each time your foot hits the ground, and it inflicts muscle damage that slows you down and leaves you sore. “A lot of people who’ve raced in these shoes say, ‘I couldn’t believe I woke up the next morning and my body didn’t ache, and I could get up and go for a run again,’” White says.

That’s been a widely reported anecdotal experience of running in this type of shoe – and it’s even backed up by a small internal study that Nike researchers presented last summer at a biomechanics symposium in Kananaskis. In 14 runners at the Portland Marathon, those who were assigned to race in the Vaporfly had lower levels of blood markers of muscle damage, by between 15 and 43 per cent, than those who wore the conventional Zoom Pegasus 34. A second part of the study found that the runners were able to sustain faster workout paces with less cumulative fatigue over the course of a week when training in the Vaporfly.

The idea that the new carbon shoes make running easier on your legs is a slam-dunk selling point, even for runners who don’t necessarily care about shaving a few minutes off their marathon times. But it also matters for a more subtle reason. The role of technology in sports has always been a topic of debate, and it’s especially sensitive in a sport like running that prides itself on its simplicity and accessibility. Shoes that cost $300 or more might seem like no big deal to cyclists, but to runners that still feels faintly obscene. If the only thing these shoes did was make you marginally faster, then it would be pretty easy to marshal support for banning them, much as high-tech swimsuits were banned a decade ago. But if they also make it a little easier to get outside, hit the roads and log some miles, and to bounce back the next day and do it all again – well, that’s harder to turn down.

Of course, actually logging a lot of training miles in a shoe like the Vaporfly, with a sticker price of $330 and a soft midsole that, by some reports, loses its bounce after at most a few hundred kilometres, isn’t very practical for most people. The explosion of new plate-based shoes means that there are now options that aren’t simply intended to be marathon racing shoes. New Balance’s FuelCell TC, for example, “will be a racing shoe for some, and an elite-performing training shoe for others,” Korell says. Its launch price of $260 is intended to make it more affordable – marginally! – compared to the higher-end marathon racing shoe that New Balance plans to release later in the year. Saucony’s Endorphin line also has multiple tiers to serve different needs: the Pro has a carbon-fibre plate, while the Speed has a cheaper and slightly heavier hard-plastic plate. Both, White says, have a midsole foam that’s durable enough for sustained regular training. Under Armour’s Machina, with a composite rather than carbon-fibre plate, is also positioned as an everyday training shoe.

That’s not to say that even the fanciest high-end shoes only work for marathons. A 2018 study from researchers at Grand Valley State University pitted the Vaporfly against high-end track spikes, and found that college athletes ran 1.9 per cent faster even at distances as short as 3,000 and 5,000 metres. At the other end of the spectrum, Oklahoma-based ultra star Camille Herron has shattered world records for 100 miles and 24 hours wearing the Vaporfly. About the only thing they’re not good for, as far as we know, is handling soft or uneven surfaces like in trail and cross-country running – although when icy conditions in Buffalo forced the ncaa Northeast Regional cross-country finals to move at the last minute from a golf course to a road loop last November, a few teams rushed out to buy Vaporflys. In a huge upset, the Harvard squads, ranked fourth on the men’s side and fifth on the women’s side, won both races. Cornell’s women, ranked just 11th, snagged the second and final qualifying spot for the national championships. No prizes for guessing what shoes both those teams wore.

Last October, Eliud Kipchoge took another crack at the two-hour barrier in a non-record-eligible exhibition race in Vienna. This time he was successful, clocking 1:59:40.2. But his shoes, even thicker and more odd-looking than the Vaporfly, raised eyebrows yet again. While Nike has remained tight-lipped about them, rumours based on patent filings suggest that this new model, apparently dubbed the AlphaFly, has three different carbon-fibre plates and multiple layers of foam. Just when it seemed that the playing field was levelling out, the AlphaFly has raised fears that Nike athletes will once again be a few steps ahead of the pack at the 2020 Olympics – just as in 2016, when athletes wearing disguised prototypes of the then-unreleased Vaporfly won the women’s Olympic marathon and swept the podium in the men’s race.

The international governing body for track and field, World Athletics, has a committee that’s currently reviewing its shoe rules. There are rumours that they will impose a maximum thickness on shoe midsoles that would rule out the AlphaFly – an idea that New Balance’s Korell, for one, supports. But even without the AlphaFly, it’s not yet clear how well the new generation of carbon competitors stacks up with the Vaporfly. Unlike Nike, none of the other companies have released testing data on running economy.

Reid Coolsaet, a longtime New Balance athlete who ran the marathon at the 2012 and 2016 Olympics, had a chance to try three of the company’s carbon plate prototypes in 2019. His assessment of the third one: “Light, comfortable, and good grip. They’re a good shoe. But when I compared them to the Next% [the latest model of the Vaporfly], they didn’t feel anything like them.” Coolsaet parted ways with New Balance at the end of 2019, and plans to try the Vaporfly in his next marathon.

I’ve got a spring marathon lined up too, my first one since 2013. And, as it happens, I have an old pair of Vaporflys tucked away at the back of my closet. I received them to review back in 2017, but I only ran in them twice, for a total of about 10K. At the time, I just didn’t feel right about running in them. But I’ll be honest: I’m nervous about my marathon. In 2013, the last 10K or so was a death march with quads that shrieked in agony with every step, even though I’d logged several months of solid mileage and long runs of up to 35K. I have a bouncy middle-distance stride instead of a marathon shuffle, so running long pounds my legs and inflicts a crippling dose of what Korell calls “eccentric loading.”

I’ll be racing as fast as I can this spring, and I won’t lie and say my finishing time doesn’t matter to me. But even more alluring is the thought of being able to run those last 10K – of grappling honestly with exhaustion instead of practicing my agonized audition for the Monty Python’s Ministry of Silly Walks. I don’t know whether a thick wedge of foam with a carbon plate inside will make that dream come true. But I’m planning to dust off those old Vaporflys to find out – and I suspect that, when I look around on the start line, I’ll discover that I’m just one of the crowd.

This story originally appeared in the March & April 2020 issue of Canadian Running.

Alex Hutchinson (@sweatscience) is Canadian Running’s longtime ‘The Science of Running’ columnist and the author of the 2018 New York Times bestseller Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance. He lives (and runs) in Toronto’s west end. He is a former physicist who competed for the Canadian national team in track, cross-country and mountain running.