Knee pain in runners: new theories on patellofemoral pain syndrome

Why the clamshell exercise may not be helping

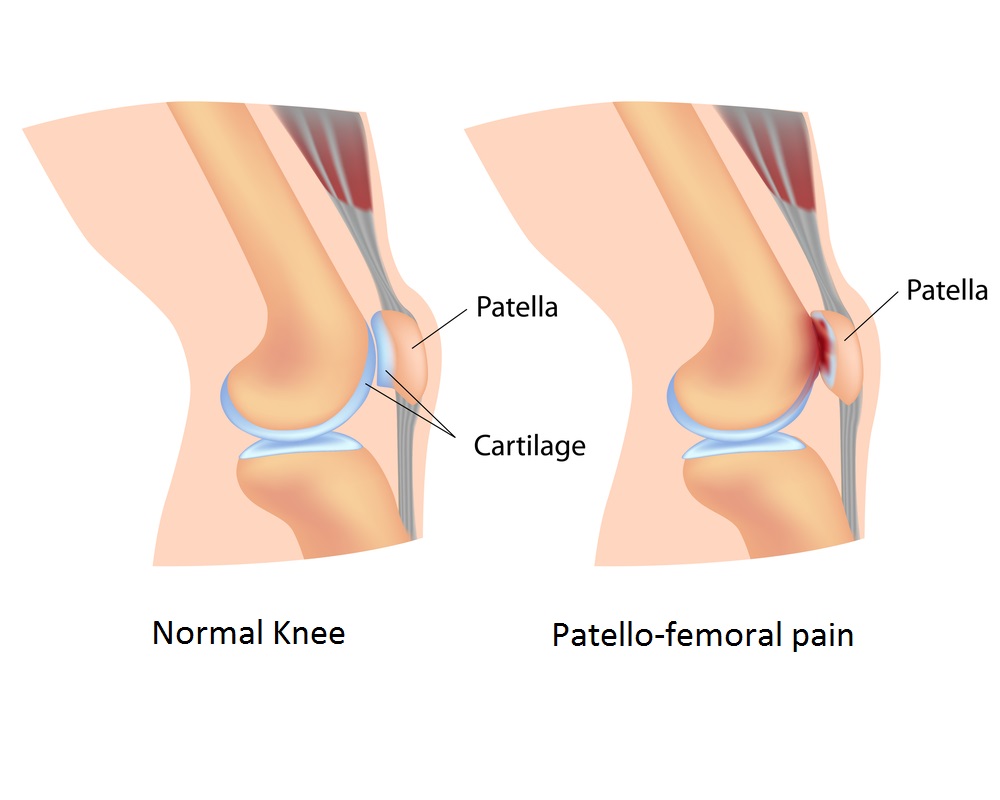

A hot topic in sports medicine right now, PFPS (patellofemoral pain syndrome) is the most common type of knee pain runners. An achy feeling around the centre of the kneecap, or patella, PFPS can interfere with training, and even non-running activities such as climbing stairs or playing tennis. Fortunately, ongoing research is leading to better protocols for treating it so you can get back on the roads and trails pain-free ASAP.

We spoke to physiotherapist Chris Napier of Vancouver about PFPS, the most likely causes, and how runners can help themselves. In addition to being a marathoner himself, Napier has a Ph.D. in running biomechanics and a diploma in sport physiotherapy. Here’s what he had to say about PFPS.

Get an accurate diagnosis

Get an accurate diagnosis

Napier cautions that PFPS is not the only possible cause of knee pain in runners, just the most common cause. (Pain on the outside of the knee is more likely related to the IT band. Patella tendonopathy is a different diagnosis altogether, requiring different treatment.) If you’re not sure which type of knee pain you have, a qualified physiotherapist should be able to quickly diagnose and treat it. If you’ve never been to a physio, ask around among your fellow runners and look for someone who is not only well qualified, but who is a runner, or at least supportive of runners resuming training as quickly as possible. Also, a physio with a sport rehabilitation diploma or certificate has spent hundreds of hours with athletes and understands training loads. “I rarely ever tell someone to stop running,” says Napier. “It’s usually better to manage the training load than to stop altogether.”

RELATED: Chris Napier recounts “dream trip” to Uganda as Team Canada’s physiotherapist

How PFPS theories evolved

Twenty years ago, Napier explains, PFPS was thought to be due to poor tracking of the kneecap in the “tracks” of the femur (thigh bone), and the fix was strengthening the quadriceps to keep the kneecap properly aligned.

Later, the emphasis switched to the hip, the new theory being that the femur was rotating inward during the stride, causing the “tracks” to move and miss catching the kneecap. This internal rotation, or adduction, causes the knees to buckle inward, so the emphasis in rehabilitation shifted to strengthening the muscles of the hip, rather than the quads. It’s the job of the gluteus medius to abduct the femur, i.e. to keep it rotated outward, so when a runner is fatigued after many miles, weak glutes would fail to prevent this inward rotation of the femur, causing the knees to cave in, resulting in pain.

However, some experts questioned whether weak glutes might just be another symptom, rather than the cause of knee pain. The most recent consensus statement on the subject, to be published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, will recommend strengthening both the gluteal muscles and the muscles around the knee.

Practical tips

Some kind of gait retraining may be necessary, e.g. keeping the knees slightly further apart and increasing the cadence (number of steps taken per minute). If your cadence is 175 or less, try to increase it by five to ten per cent. (Some GPS watches will record your cadence.) The idea is to reduce stance time, or the length of time the foot is in contact with the ground, to reduce the time available for the femur to rotate inward.

Napier says this will feel strange at first, because our brains become accustomed to running in a way that feels natural for us, but after practising for a month or two it feels less awkward. Many runners will notice a difference in their pain almost right away, which can motivate them to continue to practise.

Napier also talks to patients about their training load, possibly recommending taking things easier for a few weeks, and avoiding spikes in training volume. He might also suggest looking for softer surfaces to run on, and teach patients how to recognize when it’s ok to run through pain and when they should stop.

The best exercise for PFPS is NOT the clamshell, Napier points out. (The clamshell is the exercise done lying on your side with your feet together and knees bent, opening and closing your knees.) Why? Three reasons: the load is very low, the action is not something that happens during running, and it’s not weight-bearing.

What’s needed is a single leg position, such as single-leg squats, using a mirror to make sure your knee stays straight and your hips are not dropping or turning in. An even better one is to stand on one leg on a step and hop down onto the ground, then step back up (with the other foot first). In this exercise the glutes are in a weight-bearing position and your foot is in contact with the ground, as it is when your knee hurts during running. When you land, bend your knee only as much as you normally would during running, i.e. not more than about 45 degrees.

When you can do three or four sets of eight to ten reps, try adding weight by holding an eight or ten pound dumbbell or kettlebell. Napier recommends increasing the weight before increasing reps.

What about orthotics?

Napier reports that the latest consensus statement mentioned earlier will suggest that orthotics may help with pain in the short term, but they are not a long-term solution if the real issue is muscle weakness. Furthermore, they do not have to be custom-made. Inexpensive, off-the shelf shoe inserts from the drugstore are fine.

Get an accurate diagnosis

Get an accurate diagnosis